CHAPTER SIX

From the dawn of European Union consumer policy, the focus was on enabling ‘consumers, as far as possible, to make better use of their resources, to have a freer choice between the various products or services offered’.1 One of the main priorities was to ensure protection against ‘forms of advertising which encroach on the individual freedom of consumers’.2 Emphasis was laid on ‘consumer information and education’ which, inter alia, means that information should be made available to the purchaser of goods or services to enable him to ‘make a rational choice between competing products and services’ in order to ‘benefit from basic information on the principles of modern economics’.3

1. Empowerment

Human agency and the right to self-determination are central concepts in legal theory as well as in consumer protection law, where the regulatory framework is aimed at empowering consumers to act in accordance with their preferences.4 Empowerment also permeates data protection law, with consent possibly being the clearest example that elucidates the interplay with transparency.

Empowerment in data protection law does not mean that data subjects have absolute control over what data are being processed about them, nor by whom. The processing of personal data must be ‘lawful’ no matter what legitimate basis is relied on. In the case of data-driven business models that are offered to consumers, this must require that the activity also be in compliance with the UCPD.

1.1. Agency, autonomy and free will

To avoid too much of a philosophical detour, we will make the assumption that (1) human beings have agency,5 consisting of autonomy and a free will, and (2) that this agency is limited by certain filters, including perception, intelligence and ignorance.6 In the context of ‘free will’, we must recognise that a person is ‘a mixture of conscious and unconscious components’,7 and that around 98 percent of what our brains are doing is said to be below the level of consciousness.8

We do not take on the task of grappling with the subtle differences between agency, autonomy and free will, but assume, as expressed by Barry Schwartz, that ‘every choice we make is a testament to our autonomy, to our sense of self-determination.’9 We do not enter into discussions about how privileges and money affect autonomy.10

Both data protection law and marketing law rely on human agency. The consumer is assumed to make informed (efficient) choices, i.e. exercising due care. In data protection law, the data subject must take decisions with regard to consent as well as other decisions that have privacy implications.

1.2. The right to self-determination

It has been argued—with reference to German law—that the right to self-determination is ‘the most important constitutional fundamental right for consumers’ as it guarantees ‘the fundamental freedom for a person to develop his own personality (“Freie Entfaltung der Persönlichkeit”) or private autonomy (“Privatautonomie”)’.11

The concept of informational self-determination has been mentioned in the context of consumer law12 and data protection law,13 including the German constitution (‘informationelle Selbstbestimmung’).14 The right to self-determination has its origins within international law and politics and is not as such explicitly recognised as ‘constitutional’ in EU consumer law, but can be derived from human dignity, as discussed in Chapter 10 (human dignity and democracy).

In international politics, the concept can be traced back to the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era.15 The concept is recognised in the first article of the 1945 Charter of the United Nations (subsection 2): ‘The Purposes of the United Nations are […] to develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, and to take other appropriate measures to strengthen universal peace’ (emphasis added).16 Self-determination can be defined as ‘the ability of the individual to freely enjoy the values of life, prosperity and status, and hence to define its destiny’,17 and the initial idea was to free peoples from (state) repression.

The right to self-determination was recognised as a human right in 1966 to ensure that everyone may enjoy civil and political rights, as well as economic, social and cultural rights, where ‘all peoples have the right of self-determination’ and ‘by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.’18 The phrase ‘all peoples’ rather than ‘everyone’ indicates that this right is a collective right and not a right that can be exercised individually.19

The right to self-determination is closely linked to additional factors such as education and information to achieve ‘individual empowerment’ and/or ‘enhanced individualization’.20 In that sense it is intended to ensure a general right to be free from oppression and to have a ‘free choice of one’s own acts or states without external compulsion’.21 This discussion is pursued in Chapter 8 (manipulation) in the context of freedom and paternalism.

2. Rational decisions

As our focus is on the regulation of markets, it is important to emphasise that economic theories underpinning markets—in addition to free choice—assume that consumers are able to make ‘informed’/‘efficient’/‘rational’ choices. Economic theory usually applies a thin rationality (‘revealed preferences’) that disregards value shaping, adaptive preferences and the interest of future generations,22 as well as the fact that people might prefer to do something other than spending time on maximising their economic interests.23

In neoclassical economics, markets are viewed from a supply and demand-perspective in accordance with rational choice theory, which provides a framework for understanding social and economic behaviour. Neoclassical economics works with three basic assumptions: People have rational preferences among outcomes that can be identified and associated with an expected value. Individuals maximise utility (as consumers) and firms maximise profit (as producers). People act independently on the basis of full and relevant information.

Rational choice theory rests on the assumption that aggregate social behaviour results from the behaviour of individual actors who make decisions in accordance with their preferences. This rational agent is expected to take into account all relevant information, potential costs and benefits etc. in order to act in accordance with his preferences.

Behavioural economics24 revolves around the economic consequences of the continuous stream of studies providing ever more fine-grained knowledge about human behaviour in general and human decision-making in particular, with a view to adjusting neoclassical economics for these insights found in behavioural sciences.

Market failures that rest on biased demand, generated by imperfectly rational consumers, have been labelled ‘behavioural market failure’;25 and these may lead to consumer loss. Behavioural sciences, as such, are not concerned with such losses or market failures, as they are merely focused on understanding human behaviour. It does not matter which sciences (psychology, neuroscience, sociology, etc.) the behavioural understanding or models originate from.

‘Behavioural law and economics’26 has been defined as seeking to ‘inform legal analysis by drawing on both the methods and the extensive findings of behavioural decision research, the psychology of judgment and decision-making, and related fields’.27 As consumer law is part of economic law, which rests on an ideal of efficient distribution in markets, as discussed in Chapter 3 (regulating markets), behavioural sciences are normally used in a behavioural economics setting in this context.

3. Bounded rationality

The brain is extraordinarily efficient, which may be illustrated by the 1997 chess match in which IBM’s Deep Blue became the first computer to defeat a reigning world chess champion (Garry Kasparov) under tournament conditions. If we perceive heat emission as a waste product from computing, Kasparov’s brain was significantly more efficient than the computer.28 Computers are improving in efficiency, but we must not forget to praise the human brain for its capacity, which goes far beyond mere data processing. Even the most advanced AI systems are ‘far below the human baseline on any reasonable metric of general intellectual ability’.29

Despite the human brain’s efficiency, its goal is to suit the overall fitness of the organism in which it is encapsulated, and not necessarily to follow economic theories,30 and it is in particular challenged when it is to evaluating symbolic values. Privacy, for instance, may in a commercial context appear both abstract and symbolic. The same is true for risks:31 Just think of a cyclist with a helmet on his head and a smartphones in his hand.

As far back as 1935 it was suggested that practically everything that people want is wanted for some unconscious (emotional) reason that the average person does not understand, and that apparent reasons are merely excuses (‘rationalisation’)32—the idea being that we find meaning in and arguments for what we do rather than doing things because we find them to be meaningful or rational in an economic sense. In this vein, Nassim Nicholas Taleb offers the advice not to do things for which you have more than one reason, because ‘by invoking more than one reason you are trying to convince yourself’.33

The term ‘bounded rationality’ encapsulates the compromise that the rationality of individuals is limited by the cognitive limitations of their minds, taking into consideration the finite amount of time they have to make decisions.34 It explores systematic biases and heuristics that separate the beliefs that people have and the choices they make from the optimal beliefs and choices assumed in rational-agent models.35

The part of behavioural sciences that is relevant in this context spans a variety of investigations of human behaviour through observations made in scientific experiments; i.e. systematic analyses, often in a naturalistic, yet controlled, environment. It includes cognitive sciences, in particular psychology,36 neuroscience37 and ‘social physics’,38 which may be used to understand and provide models for characteristic features of human behaviour, including decision-making in a broad sense and encompassing learning, the development of preferences and actual decision-taking.

The term ‘bounded rationality’ was introduced in 1955 by Nobel laureate Herbert A. Simon,39 who, by the way, also coined the term ‘attention economy’, introduced in Chapter 2 (data-driven business models), and is the ‘Father of Artificial Intelligence’.40

In the 1960s, researchers within cognitive psychology began to develop models based on the perception of the brain as an information processing device. From such a perspective, human decision-making rests on navigational input provided by two systems, denoted System 1 and System 2 by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman.41 Their features may be characterised by a number of attributes, including those listed in Figure 6.1.

System 1 |

System 2 |

Intuition Effortless Automatic Sensory Parallel Hot Social Unconscious Abstract Short-sighted Pragmatic inferences |

Reason Effortful Controlled/reflective Semantic Serial Cold Asocial Conscious/deliberate Specific Far-sighted Logical inferences |

Figure 6.1. Distinctions between fast and slow thinking.

Both systems play an important role in surviving and thriving in society. However, it is clear from many experiments that we do not fully control these systems, and, notably, that it is not possible to turn off System 1 completely in order to make rational choices,42 as envisaged in rational choice theory.

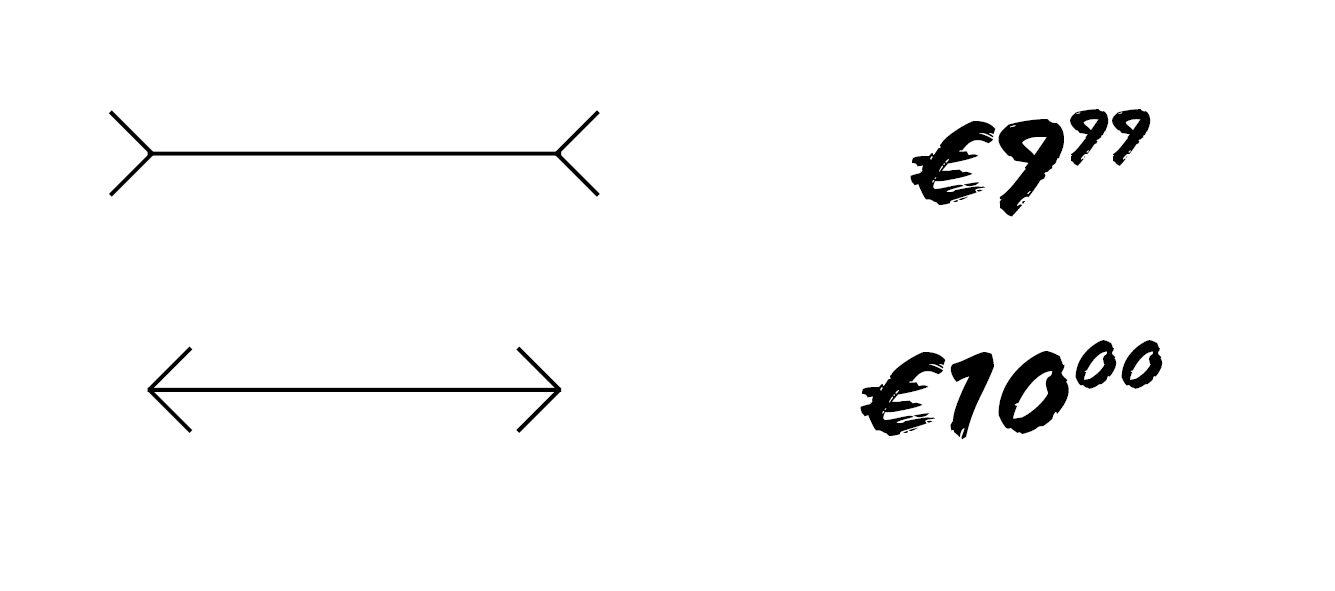

Figure

6.2. Optical illusion and ‘charm pricing’ that affect our

perception even when we are fully informed and aware of their effect.

Humans are subject to various biases and utilise a number of heuristic techniques, as the behavioural sciences make clear. Two important challenges to the rational choice theory—especially in light of the information paradigm that is discussed in Chapter 9 (transparency)—is that it ignores the fact that (1) emotions play an important role in human decision-making43 and (2) consumers must make many, often complicated choices, with time as a scarce resource.44 In general, it is fair to say that ‘human forecasts are flawed’ and that ‘human decision-making is not so great either’.45

From a consumer protection perspective, some important insights include that we humans have a bias towards the present (instant gratification and bounded willpower)46 and often make decisions based on the information that is immediately present or recent (the availability heuristic),47 thus tending to forget to ask what relevant information is missing. In addition to that, there are severe limitations as to how much information we can process (information overload).48 We also know that frequent repetition is ‘a reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods’.49

The term ‘bounded rationality’ is used to denote such deviations from rational behaviour, as assumed in rational choice theory. This includes ‘bounded willpower’,50 which is a vital but limited biological resource that can easily be depleted for temporary periods.51 As expressed by Jon Elster:

‘autonomy will have to be understood as a mere residual, as what is left after we have eliminated the desires that have been shaped by one of the mechanisms on the short list for irrational preference-formation [i.e. adaptive preference formation, preference change by framing, wishful thinking and inferential error]’.52

4. Bounded rationality and the law

In marketing law, the average consumer plays an essential role, and it intuitively seems reasonable to take bounded rationality into account when determining the effect on or reaction of a typical/an average consumer, cf. recital 18 UCPD. In the following, although we focus on the UCPD, similar arguments can be made for considering bounded rationality in the context of information and consent under the GDPR.

4.1. The average consumer

As the average consumer sets the standard for how consumers should behave, it seems reasonable to also consider research in human decision-making to particularise these expectations. The reason is simply that if we know that consumers are likely to behave in a particular way, it seems counter intuitive—especially from a consumer protection perspective—to ignore this information and expect (unrealistic) rational behaviour as envisaged in rational choice theory.

Behavioural sciences may give guidance on how consumers in general are likely to respond to particular commercial practices. Other sciences, including neuroscience, and more specific methods such as eye-tracking,53 A/B-testing54 and social physics may also be applied, to determine how consumers are likely to observe, process and respond to commercial practices, including information provided.

People are different and will react differently to commercial practices. More sophisticated individuals may be less likely to suffer negative consequences from a commercial practice that may easily trick less sophisticated consumers. In order to illustrate decision quality—both in general and following a concrete commercial practice—it may be helpful to consider consumers to be represented along a continuum that runs from very sophisticated to very vulnerable.

One could assume a normal distribution (bell-curve), but the particulars of the distribution in itself are not as relevant as the fact that it is inevitable that some consumers will be negatively affected by virtually any commercial practice—even practices elaborated in good faith. This is one reason why there must be an accepted level of ‘collateral damage’ in marketing law,55 which is also recognised in recital 18 of the Directive that states that ‘it is appropriate to protect all consumers from unfair commercial practices; however the Court of Justice has found it necessary […] to examine the effect on a notional, typical consumer’ (emphasis added).

Because the average consumer aggregates a great variety of behaviours, it must necessarily be an abstraction which does not seek to identify one person to represent the group, but rather sets the threshold for an acceptable level of due care to be exercised by consumers. In other words, the law does not protect consumers who fail to exercise this particular level of care.

Consumers fail to exercise the care expected of the average consumer for many reasons, including in particular a decision not to, e.g., read information, and an inability to, e.g., understand information, both of which prevent them from acting above the expected threshold. In between these extremes are situations where consumers suffer from occasional ‘attention deficit’; where even salient details are overlooked or otherwise clear information misunderstood. This applies equally to commercial conducts when consumers fail to recognise them or understand their implications.

The UCPD does not make a distinction among these situations, so consumers who fail to meet the average consumer standard are treated the same way no matter whether the reason is laziness, time constraints or cognitive limitations. As argued above, it seems obvious to consult available insights on consumer behaviour—which is often of a statistical (descriptive) nature56—when setting the standard for due care that the average consumer is expected to exercise.

Statistical evidence may assist judges in determining likely behaviour—or reaction to a commercial practice—but notably, it cannot establish whether e.g. a commercial practice is misleading. Despite great variety in consumer behaviour, the court must still reach a binary decision as to whether the commercial practice is unlawful. Through this normative assessment, the court sets a threshold for the amount of collateral damage that should generally or specifically be accepted.

Research in consumer behaviour may be applied either: (1) by testing the actual commercial practice or (2) by extracting general features of human decision-making.57 There are costs involved in both methods, but the former will usually be more cumbersome and expensive because it requires specific experiments, whereas evidence of general features of human decision-making can be found through literature studies. Even though specific experiments could be more precise—as they address the case in question—one (e.g., a judge) must still apply the results in order to establish a behaviour that can reasonably be expected from the average consumer. It should also be noted that consumer polls may not be reliable when consumers reflect on how they believe they are affected by marketing (self-reporting).58 Thus experts’ opinions relying on e.g. behavioural economics could be cheaper and equally helpful.

Using evidence of real consumer behaviour may relax requirements for the expected care exercised by the average consumer, as discussed below in the context of the Mars case. This could improve the protection of more vulnerable consumers and possibly lead to a standard closer to the abandoned German benchmark: ‘the casually observing and uncritical average consumer’.59 This definition may be more realistic, even though this standard has been ridiculed as reflecting the ‘image of an infantile, almost pathologically stupid and negligently inattentive average consumer’.60

4.2. Professional diligence

Traders are likely to have more insight in the particulars of bounded rationality than consumers do, and traders are likely to use these insights in commercial practices with a view to persuading consumers. It follows from the UCPD and preparatory works that puffery,61 product placement, brand differentiation, and the offering of incentives are accepted marketing practices. According to the proposal for the Directive, the concept of professional diligence is necessary to ensure that ‘normal business practices’ which are in conformity with custom and usage—such as the offering of incentives and advertising based on brand recognition or product placement—are not contrary to the requirement of professional diligence.62

It not clear from the context why these practices are legitimate and how the trader should obtain knowledge of this. Incentives in the guise of sales promotions are likely to utilise flaws in human decision-making, and thereby imposes a risk of distorting the economic behaviour of the average consumer. The trader is the professional party, and the standard of professional diligence could include expectations as to his knowledge of how consumers in general are likely to react to particular commercial practices—as expressly mentioned in the context of vulnerable consumers. It is on the other hand obvious that the application of behavioural sciences in the context of the average consumer is more straightforward than in this context.

In order to seek a general applied, objective standard, the Directive makes no reference to the trader’s subjective intention behind a commercial practice.63 It is, however, not the same as ruling out the possibility of considering the likely purpose (reasonably expected outcome) of particular commercial practices. In a U.K. case concerning commercial practices, it was said that:

‘[…] I believe that the defendants’ business model is designed and calculated to take advantage of the naivety and inexperience of the average consumer by using gym clubs at the lower end of the market.’64

It lies in the model of the UCPD that courts should consider both the effect (economic distortion) and professional diligence. In that vein, it could be presumed contrary to the requirement of professional diligence to use commercial practices that the trader should know are likely to distort the economic behaviour of the average consumer, taking into consideration what he as a professional trader should know about how a commercial practice is likely to affect consumer behaviour.

4.2.1. Information

Information, as we discuss in Chapter 9 (transparency), always entails a risk of disappointment, and saying more is not always the solution, as it may impact the information’s effectiveness. Issues of ‘information overload’ have been recognised by the Commission, particularly in relation to the ‘small print’ of contract terms and conditions.65 To a large extent information may primarily benefit consumers who are more sophisticated than the average consumer, and who are in fact reasonably observant and circumspect. Consumers in the long tail of consumer sophistication will be less likely to read and understand the information.

In the assessment of information, it could be considered whether some of the information actually detracts from the information that the consumer should base his decision on, as any statement may be affected by the context, including other information and illustrations.66 According to the availability heuristic, we are likely to base our decisions on available information and fail to identify which additional information is missing.

In the Food Information Regulation, voluntary food information may not be displayed to the detriment of the space available for mandatory food information.67 A similar approach could e.g. be relevant in cases where the consumer is likely to spend little time on the decision (as in impulse buying, for example), or where irrelevant information is presented in a way that distracts the consumer’s attention (e.g. extraordinarily long copy when conveying important information); thus wasting precious time dedicated to understanding the details.

In the assessment of professional diligence, it could be helpful to consider possible improvements that could increase the average consumer’s understanding of the commercial practice,68 and of how difficult and/or expensive these improvements would be. The burden of proof would lie with the plaintiff, e.g. an enforcement authority, who would have to specify alternatives for the courts to consider.69 To some extent this reversed standard—to suggest improvement rather than proving failure to comply with the standard of professional diligence—is introduced in the context of misleading omissions, where the trader is required to reveal information that is material for the consumer to take an informed transactional decision; and where the plaintiff may argue that omitted information is material.

In particular, the requirement of disclosing information or re-designing the choice architecture may be greater when the commercial practices is likely to take advantage of bounded rationality. In general there is no economic reason not to require traders to increase (or decrease) the amount of information useful for consumers to make more informed choices—i.e. if they can correct inadequate levels of information on the part of consumers in a cost-effective way, their practices could be presumed unfair if they do not engage in these educational or corrective actions.70

Ideally, marketing should convey information that is meaningful for the decision that the consumer is about to make. The yardstick for marketing could—having regard to insights into human decision-making—be based on an analysis of the extent to which the information is likely to assist or distract consumers, expecting e.g. salient information to be consistent with the fine print.71

4.2.2. Aggressive commercial practices

Commercial conducts are aggressive if they are likely to impair the average consumer’s freedom of choice by harassment, coercion, including the use of physical force, or undue influence. It could, in particular, be considered whether the trader’s exploitation of bounded rationality or bounded willpower could amount to undue influence, which is defined as ‘exploiting a position of power in relation to the consumer so as to apply pressure, even without using or threatening to use physical force, in a way which significantly limits the consumer’s ability to make an informed decision’.72 As mentioned above, traders are—in contrast to consumers—often well-informed about consumers’ biases and heuristics.

An illustrative example can be found in several airports where visitors, in order to get to their gates, are forced to wander through a shop immediately after security—sometimes with a somewhat concealed escape route for people with allergies. This is a behaviourally informed—and probably profitable—nudge to make visitors spend more time and money in the store. This solution allows travellers, who intend to buy, to get to their gates faster, but it is not unlikely that at least some visitors will take a transactional decision that they would not have taken otherwise.

In determining whether a commercial practice uses undue influence, it follows from Article 9 UCPD that account shall be taken of, inter alia, its timing, location, nature or persistence, and the exploitation by the trader of any specific misfortune or circumstance of such gravity as to impair the consumer’s judgement, of which the trader is aware, to influence the consumer’s decision with regard to the product. Thus, at least in some instances the exploitation of known flaws in human decision-making must be contrary to the requirement of professional diligence.

4.3. The CJEU’s application of behavioural sciences

Historically, the CJEU has favoured consumers’ logical inferences rather than their pragmatic (emotional) inferences.73 This can be illustrated by the Mars case74 where the marking of ‘+ 10%’ on the wrapping of ice-cream bars occupied approximately 30 percent of the total surface area of the wrapping.75 The Court found that the average consumer was expected to know that there is not necessarily a link between the size of publicity markings (relating to an increase in a product’s quantity) and the size of that increase76—thus ignoring likely pragmatic inferences from the package design. In that vein it should be emphasised that pictures are more efficient in conveying information77 than written letters that need to be processed.78

An experiment has shown that consumers overestimate the extra volume when confronted with an oversized indication.79 A subsequent study did not produce empirical evidence of a clear influence on the transactional decision of consumers.80

There is substantial focus on behavioural sciences in a consumer law context in the European Union (and elsewhere), including in the guise of ‘nudge units’. The European Parliament has suggested that targeted funding be allocated to consumer research projects, especially in the field of consumer behaviour and data collection, to help design policies that meet the needs of consumers.81 The CJEU has not (yet, explicitly) adopted behavioural sciences in its case law, but it has in the context of aggressive practices in the Directive’s Annex recognised that traders may exploit psychological effects in order to induce the consumer to make a choice which is not always rational.82

The Commission, in its first staff working document concerning the UCPD,83 has acknowledged that the understanding of consumers’ skills, knowledge and assertiveness is essential if consumer policy measures are to correspond to their actual daily behaviour, as opposed to textbook models of what they do. In the current Staff Working Document it is emphasised—in the context of misleading commercial practices—that ‘insights from behavioural economics show that not only the content of the information provided, but also the way the information is presented can have a significant impact on how consumers respond to it’, and ‘for this reason, Article 6 explicitly covers situations where commercial practices are likely to deceive consumers “in any way, including overall presentation” even if the information provided is factually correct’.84

In the context of food labelling, the CJEU assumes that consumers whose purchasing decisions depend on the composition of the products in question will first read the mandatory disclosures in the list of ingredients.85 However, in the Teekanne case,86 the Court emphasised that the assessment of whether labelling is misleading must take into account ‘the words and depictions used as well as the location, size, colour, font, language, syntax and punctuation of the various elements on the fruit tea’s packaging’.87

The case concerned the packaging of a fruit tea (‘Felix raspberry and vanilla adventure’) which inter alia comprised (1) depictions of raspberries and vanilla flowers, (2) the indication ‘fruit tea with natural flavourings’, and (3) a seal with the indication ‘only natural ingredients’. The fruit tea did not contain any vanilla or raspberry constituents or flavourings, and the list of ingredients correctly stated that it contained ‘natural flavouring with a taste of’ (emphasis added) inter alia vanilla and raspberry. The CJEU stated that even a correct list of ingredients ‘may in some situations’ not be capable of sufficiently correcting the consumer’s erroneous or misleading impression that stems from other items on the packaging.

Even though it could seem like the CJEU recognises findings within behavioural sciences, the Teekanne decision could also be seen as a confirmation that a list of ingredients, normally, can correct misleading statements seen elsewhere on the product—even though depictions on the packaging are likely to have much greater influence on consumer choices than the list of ingredients.

The average consumer standard can be said to establish a reasonable level of cognitive ability and a reasonable time that the consumer should spend on gathering and understanding information. This is clear from an Advocate General’s assumption that the average consumer is expected to spend the time to take note of the information on a food label (before acquiring the product for the first time) and that he has the cognitive ability to assess the value of that information.88 In a similar case the average consumer was not found to be misled by the term ‘naturally pure’ (‘naturrein’) on the label of a strawberry jam which contained pectin gelling agent as an additive, the presence of which was duly indicated on the ingredient list.89

In the field of trademark law, which also incorporates the average consumer, there has been particular focus on the level of attention. In the Procter & Gamble case,90 the court established that the average consumer’s level of attention is likely to vary according to the category of goods or services in question,91 and that ‘the level of attention given by the average consumer to the shape and pattern of washing machine and dishwasher tablets, being everyday consumer goods, is not high’. This focus on likely attention could also be applied in the context of commercial practices—which is closely related to trademark law—by recognising that many choices are more emotional than rational and that consumers actually spend little time reading information.

The flexible nature of the provisions found in the UCPD allows courts to take behavioural sciences into account.92 There is, however, no substantial evidence that a behavioural turn is found in case law of the CJEU concerning unfair commercial practices. The two decisions concerning the level and nature of attention could be perceived as small steps towards the CJEU’s recognition and application of findings within behavioural sciences; possible first steps away from the ‘information paradigm’ towards a broader ‘communication paradigm’, as we discuss in Chapter 9 (transparency). Future case law will reveal the trajectory of applying behavioural sciences, and future revision of the UCPD should, under all circumstances, be more explicit on this matter.

5. Preference formation

Normally, we focus on rationality in a ‘thin’ concept, assuming that rationality is acting in accordance with our preferences, i.e. revealed preferences. In the broad concept of rationality, we must also consider rationality within preference formation—which is far more complicated.93

Decision-making is complex,94 and it is difficult to form and follow goals, values and preferences through the many dimensions of products that satisfy various aspects of our preferences (reflecting goals and values) in different ways. Consumers often have conflicting goals, values and preferences, which could be an argument for understanding our brains from a quantum physics perspective rather than in terms of classical (logic) computing. ‘Cognitive dissonance’ may lead to ignoring information that is contradictory to an existing belief.95 For instance, a person may care strongly about climate changes and still be likely to fly, and the possibility of carbon offsetting may let us feel better about such a decision. ‘Adaptive preferences’ (‘sour grapes’) is one mechanism for dissonance reduction among others.96 In general, making efficient decisions relies on consumers’ ability to overcome:

search costs (the cost of gathering and comparing information and predicting utility),

switching costs (the cost of changing providers and testing new brands or products), and

bounded rationality (biases, heuristics and other limitations to rational decision-making).

Research indicates that consumers have difficulty in choosing products that best fit their stated preferences despite truthful information,97 and it remains fair to say that, in general, we are bad at knowing what makes us happy.98 Biases and heuristics may in this light be seen as a necessary short-cut for survival, and probably the reason why most people, after all, often manage to make some relatively good choices.99

5.1. Storytelling and framing effects

The greatest achievement of the human brain may be its ability to imagine things that do not exist (our capacity for ideas), which allows us to anticipate the future.100 It is hard to overestimate the role of narratives in this vein. Storytelling is what we tell ourselves and others, and what makes it easier to live in a complicated world.101 It is a fallacy that ‘is associated with our vulnerability to over-interpretation and our predilection for compact stories over raw truths’.102

In his account of the role of intersubjectivity throughout history, Yuval Noah Harari emphasises that ‘many of history’s most important drivers are inter-subjective: law, money, gods, nations’;103 i.e. they exist in reality because we have faith in them. We could add cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens to the list.

Frames are the words and images and interactions that reinforce personal biases,104 and framing effects are closely related to storytelling,105 which is important for intersubjectivity106 and is utilised in both political107 and commercial marketing.108 As observed by Daniel Kahneman:109 ‘Framing effects are not a laboratory curiosity, but a ubiquitous reality.’ As an example, it has been proven that when identical options are described in different terms, people often shift their choices. For example, if a choice is described in terms of gains, it is often treated differently than if it is described in terms of losses.110 This shift demonstrates the concept and power of framing.

5.2. Cognitive overload and rational apathy

Decisions are a function of a number of decision rules, including human limitations (motivation, knowledge and ability), circumstances (opportunity, time pressure, distraction and presentation), and the nature of the decision (importance and frequency).111

The less experience and knowledge we have, the more information we may need to comprehend the information in the context of our goal, values and preferences in order to make good decisions. For markets to be efficient, consumers must be both active and competent—which entails not only that consumers have cognitive abilities to make efficient choices, but also that they take the time to make such decisions.

Consumers must make a tremendous number of decisions every day.112 Transactional decisions—the term used in the UCPD—are expected, in general, to be based on the consumer’s goals, experience and available information. In order for consumers to make decisions that match their goals, values and preferences, they process available information and react to conducts based on both a logical and emotional response. A rational decision relies on both time and cognitive abilities (the consumer’s ‘processing power’ or ‘bandwidth’).113 Both factors are available in limited amounts for all purchase decisions, and the availability will depend on both the consumer (spent time and cognitive bandwidth) and the circumstances (e.g. urgency and complexity).

As decision-quality to a large extent relies on both cognitive power and time spent on making the decision, it is obvious that consumers influence decision-quality by the time and attention they devote to the decision. Research within behavioural sciences may be used when considering how much time the average consumer is expected to spend on their decisions.114 It is, for instance, found that many choices in stores are based on brand names alone,115 and often consumers do not look at the back of product packages.116 In this vein it should be noted that longer time for consideration does not necessarily lead to better decisions.117

Emotions are important for decision-making,118 and may in certain situations be a better apparatus for decision-making than our rational minds—especially from a cost-benefit perspective. However, our emotional apparatus is designed for linear causality, which is easily fooled by randomness.119 And the more information we have, the more likely we are to drown in it.120 These insights may play an important role in determining which behaviour can reasonably be expected from an average consumer.

Cognitive overload, including choice overload and information overload, may be a function of complexity, which can be a serious problem in the context of decision-making.121 There is a cost to having an overload of choice.122 Given the limitations in time, rationality, willpower, cognition, memory and experience, it may in fact be an efficient strategy to ignore information (rational apathy or deliberate ignorance) and trust one’s intuition—especially in situations where the consumer (emotionally) has made up his mind and only seeks to rationalise the decision. These issues are only corroborated by the fact that consumers often have no ability to influence the terms of service they are presented with online. As expressed by Yuval Noah Harari:

‘In the twenty-first century censorship works by flooding people with irrelevant information. […] Today having power means knowing what to ignore.’123

6. Influencing human decision-making

Insights into human decision-making are used in marketing124 as well as in regulation,125 including in the guise of nudges. Their role in marketing is discussed below, and the latter is discussed in Chapter 8 (manipulation) in the context of paternalism.

6.1. Developments in marketing

Marketing long ago developed from being informational—i.e. based on facts—to focusing more on image, lifestyle, and storytelling.126 The latter seeks to associate a certain image or story with a brand, and it is often more difficult to determine the extent to which image and lifestyle advertising is misleading or aggressive, as such advertising usually does not convey verifiable information.

It may be difficult to consider a particular lifestyle image to be misleading, because it often conveys an emotion or a story that resonates with (is ‘framed’ to fit) certain consumers’ world-view rather than carrying actual meaning. This could be an argument for taking actually conveyed information more seriously by considering both pragmatic and logical inferences that consumers are likely to make.

It could be argued, for example, that the use of ‘natural’ imagery such as grass and flowers in the marketing of gasoline can be misleading, as it suggests that gasoline is friendly to the environment.127 Placing a product that does not need refrigeration in the refrigerated section of a supermarket is telling a subtle story about freshness.128

In addition to the shift from information to image marketing, traders have also gained access to more refined ways of targeting particular groups/segments of consumers, including by means of personal data,129 as we discuss in the following chapters. To elucidate some of the content in the advertiser’s toolbox, we make a brief introduction to some findings by Robert B. Cialdini.

6.2. Cialdini’s principles of persuasion

In his classic book, Influence, professor of psychology and marketing Robert B. Cialdini has identified seven ‘levers of influence’130 that are briefly introduced to elucidate some classical tools in the advertiser’s toolbox. This thought-provoking book comes fully equipped with strategies for defending oneself against these tactics.

Reciprocation. This is a basic norm in human culture that requires one person to try to repay what another person has provided. The rule applies even to uninvited gifts or favours, and the feeling of indebtedness may leverage substantially larger favours in return. The rule also works in situations where a request has been declined, which makes it easier for the requester to successfully ensure compliance with a smaller favour (‘rejection-then-retreat’ tactic). Thus, it may be profitable to give something or ask for a larger favour before asking the consumer for a favour.131

Liking. We prefer to say yes to individuals we like. In addition to physical attractiveness, likeability can be boosted by compliments and similarity, i.e. to people whom we believe to be like us, or to those we already know (even peripherally). Repetition increases familiarity, and thus likeability. Even association with favourable events or people will increase likeability.132

Social proof. This tactic includes making products appear popular or trending. Social proof works best under uncertainty and/or when many people approve of the product. Liking can be used to further increase this effect.133

Authority. Use of an authority—or just symbols such as titles and uniforms—in marketing may work as a mental shortcut for quality, approval and recommendation.134

Scarcity. When something is less available, we lose freedom (of choice). Due to loss aversion, we assign more value to opportunities that are less available. The tactic is used by stating that availability is limited or by providing deadlines. We are more susceptible to this tactic if we have to compete with others, as in ‘two people from Denmark are also looking at this limited offer’.135

Commitment and consistency. We are more willing to agree to requests when we have given an initial commitment. This is because we want to appear consistent within our words, beliefs, attitudes and deeds. A reminder may restore and intensify an initial commitment.136

Unity. This principle is about establishing a ‘we’-ness in tribes that leads to group solidarity, i.e. increased agreement with and influence from members of this tribe. Shared identities may be based on kinship, geography, tastes, etc. This may also include being ‘friends’ on social media.137

It may be added that successful traders create partnerships with their consumers,138 including by offering protection and privilege,139 to create loyalty.140 However, it has also been observed that loyalty rewards are increasingly being used for tracking ‘instead of being a straightforward tit for tat based on frequent visits’,141 and that it entails that all consumers pay slightly higher prices, and only members are getting small subsidies from merchants and all other customers.142

1. Council Resolution of 14 April 1975 on a preliminary programme of the European Economic Community for a consumer protection and information policy and Preliminary programme of the European Economic Community for a consumer protection and information policy, 25 April 1975, Official Journal, C 92, pp. 1–16, paragraph 8.

2. Ibid., paragraph 30.

3. Ibid., paragraphs 34 and 42.

4. See, for instance, European Commission, ‘EU Consumer Policy strategy 2007–2013—Empowering consumers, enhancing their welfare, effectively protecting them’, 13 March 2007, COM(2007) 99 final.

5. See about agency and autonomy: e.g., Onora O’Neill, Bounds of Justice (Cambridge University Press 2000), pp. 29–49.

6. See also Jon Elster, Sour Grapes (Cambridge University Press 2016, first published 1983).

7. Susan Pockett, ‘The concept of free will: philosophy, neuroscience and the law’, Behavioural Sciences and the Law, 2007, pp. 281–293.

8. George Lakoff, [The All New] Don’t Think of an Elephant (Chelsea Green Publishing 2014, first published 2004), p. XI.

9. Barry Schwartz, The Paradox of Choice (Ecco 2016, first published 2004), p. 105. See also B. F. Skinner, Beyond Freedom and Dignity (Alfred A. Knopf 1971). Skinner regarded free will to be an illusion; see similarly Sam Harris, Free Will (Free Press 2012).

10. See, for instance, Hartmut Rosa, Resonance (translated by James C. Wagner, Polity Press 2019, first published 2016), p. 19; and Michael J. Sandel, The Tyranny of Merit (Allen Lane 2020).

11. Jules Stuyck, ‘European Consumer Law After the Treaty of Amsterdam: Consumer Policy In or Beyond the Internal Market?’, Common Market Law Review, 2000, pp. 367–400, with reference to Josef Drexl, Die wirtschaftliche Selbstbestimmung des Verbrauchers (Habilitationschrift, J.C.B. Mohr 1998) and the German constitution. See also Jules Stuyck, Evelyne Terryn & Tom van Dyck, ‘Confidence Through Fairness? The New Directive on Unfair Business-to-Business Commercial Practices in the Internal Market’, Common Market Law Review, 2006, pp. 107–152, p. 107.

12. Advocate General Trstenjak’s opinion in Case C‑540/08, Mediaprint Zeitungs- und Zeitschriftenverlag, ECLI:EU:C:2010:161, footnotes 77 and 79.

13. Advocate General Cruz Villalón’s opinion in Case C‑293/12, Digital Rights Ireland, ECLI:EU:C:2013:845, paragraph 57.

14. Antoinette Rouvroy & Yves Poullet, ‘The Right to Informational Self-Determination and the Value of Self-Development: Reassessing the Importance of Privacy for Democracy’, in Serge Gutwirth, Yves Poullet, Paul De Hert, Cécile de Terwangne & Sjaak Nouwt (eds), Reinventing Data Protection? (Springer 2009), pp. 45–76. Referring to the German Federal Constitutional Court’s Avant-Garde decision in December 1983. See also Unabhängiges Landeszentrum für Datenschutz Schleswig-Holstein, Erhöhung des Datenschutzniveaus zugunsten der Verbraucher (April 2006), pp. 15–17.

15. Wolfgang Danspeckgruber, ‘Self-Determination in Our Time: Reflections on Perception, Globalization and Change’, in Jörg Fisch (ed.), Die Verteilung der Welt. Selbstbestimmung und das Selbstbestimmungsrecht der Völker The world divided. Self-Determination and the Right of Peoples to Self-Determination (R. Oldenbourg Verlag 2011), pp 307–332, p. 311.

16. Charter of the United Nations, Article 1(2).

17. Wolfgang Danspeckgruber, ‘Self-Determination in Our Time: Reflections on Perception, Globalization and Change’, in Jörg Fisch (ed), Die Verteilung der Welt. Selbstbestimmung und das Selbstbestimmungsrecht der Völker The world divided. Self-Determination and the Right of Peoples to Self-Determination (R. Oldenbourg Verlag 2011), pp 307–332, p. 308.

18. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (opened for signature, ratification and accession on 16 December 1966; entry into force 23 March 1976).

19. See, e.g., <https://minorityrights.org/our-work/law-legal-cases-introduction/self-determination/>.

20. Wolfgang Danspeckgruber, ‘Self-Determination in Our Time: Reflections on Perception, Globalization and Change’, in Jörg Fisch (ed.), Die Verteilung der Welt. Selbstbestimmung und das Selbstbestimmungsrecht der Völker The world divided. Self-Determination and the Right of Peoples to Self-Determination (R. Oldenbourg Verlag 2011), pp 307–332, p. 309.

21. <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/self-determination> (visited February 2020).

22. Jon Elster, Sour Grapes (Cambridge University Press 2016, first published 1983), p. 36.

23. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan (2nd edition, Random House 2010, first published 2007), p. 184

24. See in general the discussions in Richard A. Posner, ‘Rational Choice, Behavioral Economics, and the Law’, 50 Stanford Law Review, 1997, pp. 1551–1575; and Christine Jolls, Cass R. Sunstein & Richard Thaler, ‘Theories and Tropes: A Reply to Posner and Kelman’, 50 Stanford Law Review, 1998, pp. 1593–1608.

25. See e.g. Oren Bar-Gill, Seduction by contract (Oxford University Press 2012), p. 2 et seq.

26. See in general E. Zamir & D. Teichman (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Behavioural Economics (Oxford University Press 2014); D. Kahneman, P. Slovic & A. Tversky (eds), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases (Cambridge University Press 1982); and Francesco Parisi & Vernon L. Smith (eds), The Law and Economics of Irrational Behaviour (Stanford University Press 2005). See also Ian Ramsay, Consumer Law and Policy (3rd edition, Hart Publishing 2012), chapter 2.

27. Avishalom Tor, ‘The Next Generation of Behavioural Law and Economics’, in Klaus Mathis (ed.), European Perspectives on Behavioural Law and Economics (Springer 2015), chapter 2 with references.

28. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deep_Blue_versus_Garry_Kasparov>. See also <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AlphaGo>.

29. Nick Bostrom, Superintelligence (Oxford University Press 2014), p. 63.

30. Read Montague, Your Brain is (Almost) Perfect (Plume 2007), p. 20.

31. See also David Ropeik, How Risky Is It, Really? (McGraw-Hill 2010).

32. Donald A. Laird, What Makes People Buy (McGraw-Hill 1935), pp. 22–21. See also Jon Elster, Sour Grapes (Cambridge University Press 2016, first published 1983), p. 124.

33. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Antifragile (Random House 2012), p. 308.

34. See in general Daniel Kahneman, ‘Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics’, The American Economic Review, 2003, pp. 1449–1475; and Bryan D. Jones, ‘Bounded Rationality’, Annual Review of Political Science, 1999, pp. 297–321.

35. Daniel Kahneman, ‘Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics’, The American Economic Review, 2003, pp. 1449–1475, p. 1449. For a more critical approach, see Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Skin in the Game (Random 2018).

36. See Daniel Kahneman, ‘Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for behavioral economics’, The American Economic Review, 2003, pp. 1449–1475; and Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2011).

37. See in particular Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error (Penguin Books 2005); Read Montague, ‘Neuroeconomics: A view from neuroscience’, Functional Neurology, 2007, pp. 219–234; and Flemming Hansen & Sverre Riis Christensen, Emotions, Advertising and Consumer Choice (CBS Press 2007).

38. See Alex Pentland, Social Physics (Penguin 2014).

39. See also Herbert A. Simon, ‘A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1955, pp. 99–118; reprinted in Herbert A. Simon, Models of man: Mathematical essays on Rational Human Behaviour in a social setting (John Wiley & sons 1957).

40. See Herbert A. Simon, Models of My Life (Basic Books 1991) and Herbert A. Simon, The Sciences of the Artifical (3rd edition, MIT 1996, first published 1969).

41. Daniel Kahneman, ‘Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for behavioral economics’, The American Economic Review, 2003, pp. 1449–1475, p. 1449.

42. See in general e.g. Walter Mischel, The Marshmallow test (Little, Brown & Company 2014) and Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2011).

43. Douglas Rushkoff, Coercion (Riverhead 1999), p. 42.

44. See Sendhil Mullainathan & Eldar Shafir, Scarcity (Times Books 2013).

45. Richard H. Thaler & Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge—The Final Edition (Yale University Press 2021, first published 2008), p. 10.

46. W. Mischel, E. Ebbesen, E. & A. Zeiss, ‘Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 21(2), 1972, pp. 204–218; and D. Read & B. Leeuwen, ‘Predicting Hunger: The Effects of Appetite and Delay on Choice’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Volume 76, Issue 2, 1998, pp. 189–205.

47. Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2011), chapters 12 and 13; and D. Kahneman, P. Slovic & A. Tversky (eds), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases (Cambridge University Press 1982), Part IV.

48. Jacob Jacoby, ‘Perspectives on information overload’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 10, No. 4, 1984, pp. 432–435; and Fernando Gómez, ‘The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive: A Law and Economics Perspective’, Revista Para el Análises del Derecho, 2006, pp. 4–34.

49. Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2011), p. 62. This is ‘because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth’.

50. Roy F. Baumeister & John Tierney, Willpower (Penguin 2011) and Walter Mischel, The Marshmallow Test (Little, Brown 2014).

51. Roy F. Baumeister & John Tierney, Willpower (Penguin Books 2011), p. 28: ‘Ego depletion’ is describing people’s diminished capacity to regulate their thoughts, feelings and actions.

52. Jon Elster, Sour Grapes (Cambridge University Press 2016, first published 1983), pp. 24–26.

53. See e.g. Keith Rayner, ‘Eye movements and attention in reading, scene perception, and visual search’, Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 2009, pp. 1457–1506.

54. Also ‘split testing’, i.e., the process of comparing the effect of slightly different versions of, e.g., cookie consent boxes, to identify the variables that most effectively elicit a desired behaviour, such as clicking ‘OK’. See also Dan Siroker & Pete Koomen, A/B Testing (Wiley 2015).

55. Jan Trzaskowski, ‘Lawful Distortion of Consumers’ Economic Behaviour’, European Business Law Review, 2016, pp. 25–49.

56. See in particular Richard A. Posner, ‘Rational Choice, Behavioral Economics, and the Law’, 50 Stanford Law Review, 1997, pp. 1551–1575, where behavioural economics is criticised in a response to Cass R. Sunstein, Christine Jolls & Richard H. Thaler, ‘A Behavioral Approach to Law and Economics’, 50 Stanford Law Review, 1998, pp. 1471–1550. The same critique could be made for using neuroscience to describe and explain human decision-making.

57. See, e.g., Daniel Kahneman, ‘Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics’, The American Economic Review, Vol. 93, No. 5, 2003, pp. 1449–1475, p. 1469: ‘The central characteristic of agents is not that they reason poorly but that they often act intuitively. And the behavior of these agents is not guided by what they are able to compute, but by what they happen to see at a given moment.’

58. See e.g. European Commission, Consumer vulnerability across key markets in the European Union (January 2016), where both perceived and real consumer vulnerability was measured. In context of focus groups, the Hawthorne effect suggests that individuals modify their behaviour in response to their awareness of being observed.

59. See in general Bram B. Duivenvoorde, The Consumer Benchmarks in the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (Springer 2015).

60. Case C‑16/83, Prantl, ECLI:EU:C:1984:101, p. 1306.

61. Article 5(3) and recital 6 UCPD and recital 48 of the New Deal for Consumers Directive.

62. Proposal for a directive concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market, COM (2003) 356, 2003/0134 (COD), paragraph 53.

63. Case C‑388/13, UPC Magyarország, ECLI:EU:C:2015:225, paragraphs 47–48.

64. OFT v Ashbourne Management Services, [2011] EWHC 1237 (Ch), paragraph 173.

65. Commission Staff Working Paper on Consumer Empowerment, paragraph 24 and European Commission, Communication on a European Consumer Agenda—Boosting confidence and growth, COM(2012) 225, chapter 3.3. See also Jacob Jacoby, ‘Perspectives on Information Overload’, 10 Journal of Consumer Research, 1984, pp. 432–435; and proposal for a directive concerning unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices in the internal market, COM (2003) 356, 2003/0134 (COD), 14, paragraph 65.

66. Richard Craswell, ‘Taking Information Seriously: Misrepresentation and Nondisclosure in Contract Law and Elsewhere’, 92 Virginia Law Review, 2006, pp. 565–632, p. 582.

67. Regulation

1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers,

Article

37 and recital

47. See also Case C‑51/94, Commission v Germany,

ECLI:EU:C:1995:352, paragraph 40, finding—in the context of food

law—that additional particulars accompanying the trade description

must be necessary for the information of consumers.

68. Richard Craswell, ‘Interpreting Deceptive Advertising’, 65 Boston University Law Review, 1985, pp. 657–732, p. 666. In Case C‑310/15, Deroo-Blanquart, ECLI:EU:C:2016:633, paragraph 37, the CJEU attached importance to the fact that the trader had demonstrated ‘care towards the consumer’.

69. See similarly in the context of contract law Richard Craswell, ‘Taking Information Seriously: Misrepresentation and Nondisclosure in Contract Law and Elsewhere’, 92 Virginia Law Review, 2006, pp. 565–632, p. 625.

70. Fernando Gómez, ‘The Unfair Commercial Practices Directive: A Law and Economics Perspective’, Revista Para el Análises del Derecho, 2006, pp. 4–34.

71. See Case C‑195/14, Teekanne, ECLI:EU:C:2015:361, discussed below.

72. Article 2(1)(j).

73. This terminology is borrowed from Richard Craswell, ‘Interpreting Deceptive Advertising’, 65 Boston University Law Review, 1985, pp. 657–732, p. 670.

74. Case C‑470/93, Mars, ECLI:EU:C:1995:224.

75. David Kraft, ‘Advertising restriction and the Free Movement of Goods—The Case Law of the ECJ’, European Business Law Review, 2007, pp. 517–523, p. 521.

76. Paragraph 24.

77. Douglas Rushkoff, Coercion (Riverhead 1999). p. 81.

78. See, e.g. Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel (W. W. Norton & Company 2005, first published 1997), pp. 215 et seq.

79. See Kai P. Purnhagen & Erica van Herpen, ‘Can Bonus Packs Mislead Consumers? A Demonstration of How Behavioural Consumer Research Can Inform Unfair Commercial Practices Law on the Example of the ECJ’s Mars Judgement’, Journal of Consumer Policy, 2017, pp. 217–234.

80. Kai

P. Purnhagen, Erica van Herpen et al., ‘Oversized Area Indications

on Bonus Packs Fail to Affect Consumers’ Transactional

Decisions—More Experimental Evidence on the Mars Case’, Journal

of Consumer Policy, 2021, pp.

385–406.

81. European Parliament Resolution on a New Strategy for Consumer Policy, 2011/2149(INI), paragraphs 10 and 41 (7 April 2011).

82. Case C‑428/11, Purely Creative and Others, ECLI:EU:C:2012:651, paragraphs 38 and 49.

83. Guidance on the application /implementation of Directive 2005/29/EC on Unfair Commercial Practices, 3 December 2009, SEC(2009) 1666.

84. Commission Staff Working Document, p. 59.

85. Case C‑51/94, Commission v Germany, ECLI:EU:C:1995:352, paragraph 34; and Case C‑465/98, Darbo, ECLI:EU:C:2000:184, paragraph 22.

86. Case C‑195/14, Teekanne, ECLI:EU:C:2015:361. The case concerned Article 3(1)(2) of Directive 2000/13/EC (now replaced by Regulation (EU) 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers). See also Hanna Schebesta & Kai P. Purnhagen, ‘The Behaviour of the Average Consumer: A Little Less Normativity and a Little More Reality In CJEU's Case Law? Reflections on Teekanne’, European Law Review, 2016.

87. Case C‑195/14, Teekanne, ECLI:EU:C:2015:361, paragraph 43.

88. Case C‑239/02, Douwe Egberts, ECLI:EU:C:2004:445, paragraph 54.

89. Case C‑465/98, Darbo, ECLI:EU:C:2000:184.

90. Case T‑129/00, Procter & Gamble v OHMI, EU:T:2001:231, see in particular paragraph 53.

91. With reference to Case C‑342/97, Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer, ECLI:EU:C:1999:323, paragraph 26.

92. See also Anne-Lise Sibony, ‘Can EU Consumer Law Benefit from Behavioural Insights? An Analysis of the Unfair Practices Directive’, European Review of Private Law, 2014, pp. 901–942.

93. See in general Jon Elster, Sour Grapes (Cambridge University Press 2016, first published 1983).

94. See also Richard Craswell, ‘Interpreting Deceptive Advertising’, 65 Boston University Law Review, 1985, pp. 657–732, p. 684.

95. Leon Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Stanford University Press 1985, first published 1957). Cognitive dissonance is assumed to be psychologically uncomfortable, and will motivate the reduction of dissonance to achieve consonance.

96. Jon Elster, Sour Grapes (Cambridge University Press 2016, first published 1983), p. 111.

97. See e.g. Kerstin Gidlöf et al., ‘Material Distortion of Economic Behaviour and Everyday Decision Quality’, 34 Journal of Consumer Policy, 2013, p. 389. See also European Commission, Consumer vulnerability across key markets in the European Union (January 2016).

98. See, e.g., Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness (Harper Perennial 2006), p. 228: ‘The best way to predict our feelings tomorrow is to see how others are feeling today’.

99. See also Richard H. Thaler & Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge—The Final Edition (Yale University Press 2021, first published 2008), pp. 23–45, about ‘sensible shortcuts’.

100. Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness (Harper Perennial 2006), p. 5.

101. Seth Godin, All Marketers are Liars (Portfolio 2009, first published 2005).

102. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan (2nd edition, Random House 2010, first published 2007), p. 63.

103. Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens (Harper 2015), p. 117.

104. Seth Godin, All Marketers are Liars (Portfolio 2009, first published 2005), p. 51.

105. Barry Schwartz & Kenneth Sharpe, Practical Wisdom (Riverhead 2010), p. 61; and George A. Akerlof & Robert J. Shiller, Phishing for Phools (Princeton University Press 2015), pp. 41–42

106. Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus (Harper 2017), p. 150: ‘Sapiens rule the world because only they can weave an intersubjective web of meaning: a web of laws, forces, entities and places that exist purely in their common imagination.’

107. See George Lakoff, [The All New] Don’t Think of an Elephant (Chelsea Green Publishing 2014, first published 2004).

108. Douglas Rushkoff, Coercion (Riverhead 1999), p. 181; Seth Godin, All Marketers are Liars (Portfolio 2005); and George A. Akerlof & Robert J. Shiller, Phishing for Phools (Princeton University Press 2015), pp. 41–42.

109. Daniel Kahneman, ‘Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics’, The American Economic Review, Vol. 93, No. 5, 2003, pp. 1449–1475, p. 1459.

110. Daniel Kahneman, ‘Rational Choice and the Framing of Decisions’, Journal of Business, pp. S251–S278; and Bryan D. Jones, ‘Bounded Rationality’, Annual Review of Political Science, 1999, pp. 297–321.

111. See also Lisa Waddington, ‘Vulnerable and Confused: The Protection of “Vulnerable” Consumers under EU Law’, European Law Review, 2013, pp. 757–783, who notes that vulnerability has a ‘dynamic and relative nature’.

112. See in general Barry Schwartz, The Paradox of Choice (Ecco 2014). See also Marco Dani, ‘Assembling the Fractured European Consumer’, European Law Review, 2011, pp. 362–384, p. 369.

113. See also about ‘limited bandwidth’ and the struggle for insufficient resources in Sendhil Mullainathan & Eldar Shafir, Scarcity (Times Books 2013).

114. Kerstin Gidlöf et al., ‘Material Distortion of Economic Behaviour and Everyday Decision Quality’ (2013) 34 Journal of Consumer Policy, 389. See also European Commission, Consumer vulnerability across key markets in the European Union (January 2016).

115. Jacob Jacoby, R.I. Chestnut & W.A Fisher, ‘Information Acquisition in Nondurable Purchase’, 15 Journal of Marketing Research, 1978, p. 532.

116. Jesper Clement, ‘Visual Influence on In-Store Buying Decisions: An Eye-Track Experiment on the Visual Influence on Packaging Design’, 23 Journals of Marketing Management, 2007, p. 917.

117. Barry Schwartz, The Paradox of Choice (Ecco 2016, first published 2004), pp. 144 and 181.

118. Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error (Penguin 2005, first published 1994), p. 194.

119. See in general, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Fooled by Randomness (2nd edition, Random House 2004, first published 2001), pp. 179 and 197.

120. Ibid., p. 136.

121. Cass R. Sunstein, Simpler (Simon & Schuster 2013), p. 40.

122. Barry Schwartz, The Paradox of Choice (Ecco 2016, first published 2004), p. 3. See also Sheena S. Iyengar & Mark R. Lepper, ‘Rethinking the value of choice: A cultural perspective on intrinsic motivation’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1999, pp. 349–366.

123. Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus (Harper 2017), p. 402

124. See in general Dale Carnegie, How to Win Friends and Influence People (Simon & Schuster 1936); Robert B. Cialdini, Influence, New and Expanded (Harper Collins 2021, first published 1984); Douglas Rushkoff, Coercion (Riverhead 1999); and Seth Godin, All Marketers are Liars (Portfolio 2005).

125. See, e.g., Richard H. Thaler & Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge—The Final Edition (Yale University Press 2021, first published 2008) and Cass R. Sunstein, Simpler (Simon & Schuster 2013).

126. See, e.g., Douglas Rushkoff, Coercion (Riverhead 1999), p. 161; and Marty Neumeier, The Brand Gap (AIGA New Riders 2006), pp. 38–39.

127. See e.g. the Danish Consumer Ombudsman, case 08/02992, which concerned a TV ad where grass was growing out of a car that was being filled with the fuel product, and that later drove off leaving a trail of flowers followed by a the slogan: ‘5 percent less CO2. Same price—better for the environment’.

128. Seth Godin, All Marketers are Liars (Portfolio 2005), p. 147.

129. See e.g. Frederik Zuiderveen Borgesius, ‘Behavioural Sciences and the Regulation of Privacy’, in Alberto Alemanno & Anne-Lise Sibony (eds), Nudge and the Law (Hart 2015).

130. Robert B. Cialdini, Influence, New and Expanded (Harper Business 2021, first published 1984).

131. Ibid., pp. 71–72.

132. Ibid., pp. 124–135. see also Dale Carnegie, How to Win Friends and Influence People (Simon & Schuster 1936).

133. Robert B. Cialdini, Influence, New and Expanded (Harper Business 2021, first published 1984), pp. 197–198. See also about ‘herding’ in Dan Ariely, Predictably Irrational (Harper Perennial 2008) and Richard H. Thaler & Cass R. Sunstein, Nudge—The Final Edition (Yale University Press 2021, first published 2008), chapter 3.

134. Robert B. Cialdini, Influence, New and Expanded (Harper Business 2021, first published 1984), pp. 238–240.

135. Ibid., pp. 289–290.

136. Ibid., pp. 360–362.

137. Ibid., pp. 435–436.

138. Seth Godin, Tribes (Portfolio 2008) and Joseph Turow, The Aisles Have Eyes (Yale University Press 2017).

139. George P. Fletcher, Loyalty: An Essay on the Morality of Relationships (Oxford University Press 1995).

140. See, e.g., Yoram Wind & Catharine Findiesen Hays, Beyond Advertising (Wiley 2016) and Seth Godin, This Is Marketing (Portfolio, Penguin 2018).

141. Joseph Turow, The Aisles Have Eyes (Yale University Press 2017), p. 22.

142. Erik K. Clemons, New Patterns of Power and Profit (Springer 2019), p. 122.