CHAPTER FOUR

1. Privacy

Discussions about privacy are far from new,1 and privacy plays an important role in both democracy and individual autonomy, where a balance must be struck between solitude and companionship: both are necessary for developing democracy and individual agency.2

Privacy may be explained and discussed from a socio-political, psychological, historical and even evolutionary perspective, and it is important to bear in mind that law can not explain privacy as it (only) reflects the political choices made. This fact by no means makes the data protection law superfluous or unimportant.

The idea and essential elements of a right to privacy can be traced back to the end of the 19th century,3 when Samuel Warren & Louis Brandeis argued that a ‘right to be let alone’ could be established under common law in the U.S. The background was developments in technology and business, where ‘instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise’ had ‘invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life’.4 Since the publication of Warren & Brandeis’s article, the single most important publication on privacy may be Alan F. Westin’s Privacy and Freedom from 1967, in which privacy is described as:

‘[…] the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others. Viewed in terms of the relation to the individual to social participation, privacy is the voluntary and temporary withdrawal of a person from the general society through physical or psychological means, either in a state of solitude or small-group intimacy or, when among larger groups, in a condition of anonymity or reserve. The individual’s desire for privacy is never absolute, since participation in society is an equally powerful desire. Thus each individual is continually engaged in a personal adjustment process in which he balances the desire for privacy with the desire for disclosure and communication of himself to others, in light of the environmental conditions and social norms set by the society in which he lives. The individual does so in the face of pressures from the curiosity of others and from the processes of surveillance that every society sets in order to enforce its social norms.’ 5

Westin demonstrated interesting foresight by stating (in 1967) that:6

‘to be always “on” would destroy the human organism’,

‘surveillance is obviously a fundamental means of social control’, and

‘the most significant fact for the subject of privacy is that once an organization purchases a giant computer, it inevitably begins to collect more information about its employees, clients, members, taxpayers, or other persons in the interest of the organization’.

The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted in 1948 with its Article 12 providing that:

‘No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.’

The ECHR was adopted in 1950 by the member states participating in the Council of Europe. Article 8(1) reads:

1. Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.

1.1. Data protection

As the first legally binding international instrument in the field of data protection—a subset of privacy—the Council of Europe adopted in 1981 the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (also known as ‘Convention 108’).7 The purpose was to secure (Article 1):

‘for every individual, whatever his nationality or residence, respect for his rights and fundamental freedoms, and in particular his right to privacy, with regard to automatic processing of personal data relating to him (“data protection”).’

The vision of a Charter of Fundamental Rights in the European Union (the Charter) was proclaimed in 2000 and it has since 1 December 2009—with amendments—had the same legal value as the EU Treaties.8 Articles 7 and 8 provides that:

Article 7

Respect for private and family life

Everyone has the right to respect for his or her private and family life, home and communications.

Article 8

Protection of personal data

1. Everyone has the right to the protection of personal data concerning him or her.

2. Such data must be processed fairly for specified purposes and on the basis of the consent of the person concerned or some other legitimate basis laid down by law. Everyone has the right of access to data which has been collected concerning him or her, and the right to have it rectified.

3. Compliance with these rules shall be subject to control by an independent authority.

The principle stated in Article 8(1) also follows from Article 16(1) TFEU. Both the now-repealed Data Protection Directive9 and the GDPR rest on a foundation of fundamental rights and provide ‘some other legitimate basis laid down by law’ as mentioned in the first sentence of Article 8(2).10 According to Article 1 GDPR, the aim is to protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons, including in particular their right to the protection of personal data, by laying down rules relating to the processing of personal data and to the free movement11 of such data.

Data protection law is a complex subject, not so much because of a lack of clarity in the applicable provisions, but more because a complex weighing-up of interests is necessary. As it further follows from recital 4:

‘the right to the protection of personal data is not an absolute right; it must be considered in relation to its function in society and be balanced against other fundamental rights, in accordance with the principle of proportionality’.

Thus, privacy is a matter of balancing legitimate interests, including other fundamental rights—such as the freedom of expression and the right to information—that are also necessary in a democracy. This is pursued in Chapter 10 (human dignity and democracy) where we also discuss the application of fundamental rights to non-state actors. For now, it is sufficient to acknowledge that the GDPR is directly applicable to businesses’ processing of personal data.12

2. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

2.1. Scope of application and interpretation

The GDPR applies to ‘processing’ of personal data, which is information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (the ‘data subject’). Personal data ‘relates’ to the data subject ‘where the information, by reason of its content, purpose or effect, is linked to a particular person.’13 Processing covers ‘any operation’ performed on personal data, including collection, use, disclosure and deletion.

The GDPR must be complied with by the ‘data controller’, which is the natural or legal person who—alone or jointly with others—determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data.14

The territorial scope of the GDPR includes (1) data controllers established in the European Union and (2) the processing of data concerning data subjects in the European Union with a view to offering products or monitoring behaviour within the Union, even when the data controller is not established within the Union.

Despite the importance of privacy and the processing of personal data, there are still only a limited amount of case law from the CJEU on this subject. Given the continuity of principles, case law concerning the 1995 Data Protection Directive remains relevant for the GDPR. In the absence of case law, inspiration can be drawn from guidelines and recommendations from the EDPB, whose interpretations are not authoritative (binding), but often serve as valuable guidelines.15

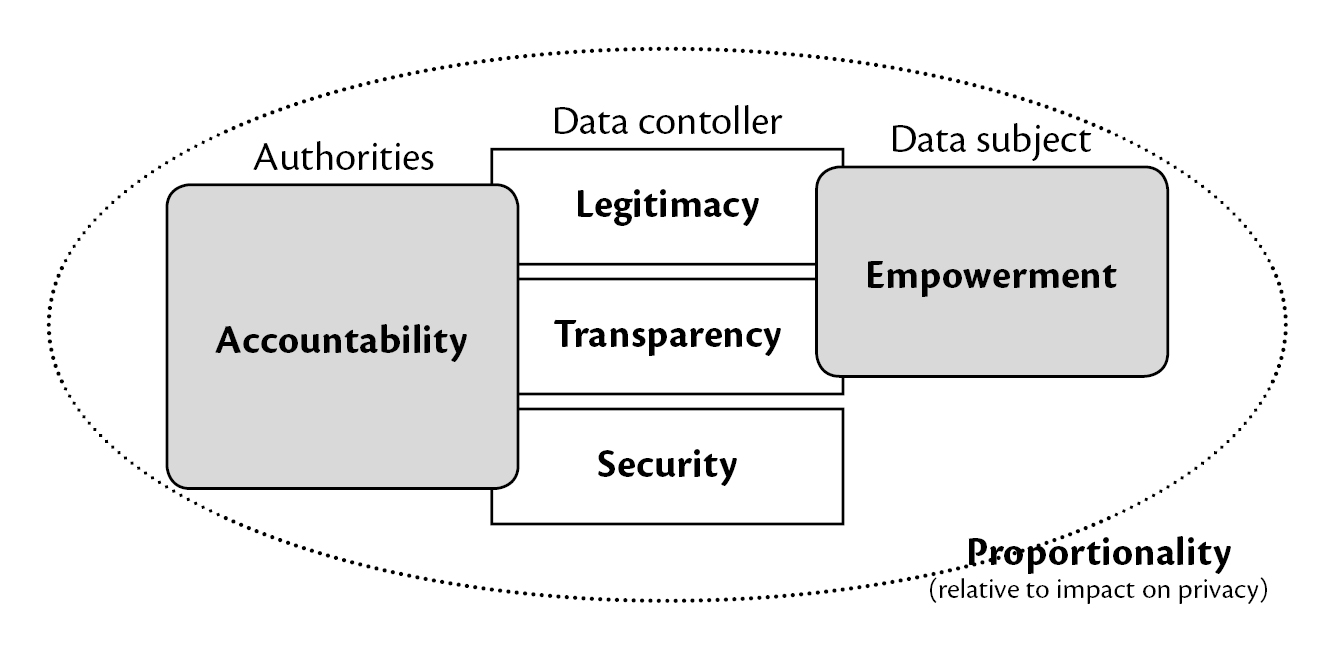

2.2. Six principles

In the following, we will distil the 99 articles and 173 recitals of the GDPR into six overarching principles—of more or less equal importance.16 The six principles (legitimacy, proportionality, empowerment, transparency, accountability and security) can be illustrated like this:

Figure

4.1. The data controller must—subject to the principle of

proportionality—ensure legitimacy, transparency and security to

demonstrate accountability and ensure empowerment of the data

subject.17

The principles overlap, and may, ultimately, be reduced to a mere matter of ‘due diligence’. For compliance purposes, the principles can roughly be grouped into three pairs:

lawful processing (legitimacy, including proportionality);

data controller’s obligations (accountability, including security);

data subject’s rights (empowerment, including transparency).

2.2.1. Legitimacy

Personal data may be processed for legitimate purposes that are specified and explicit (‘purpose limitation’). The collected data may not be further processed in a manner that is incompatible with the purposes for which the data were collected (Article 5(1)(b)). In this vein it is important to emphasise that marketing is indeed a legitimate purpose that, as mentioned in the previous chapter, is important for efficient markets.

Legitimacy may be perceived as the overarching principle that includes the general requirement of fair and lawful processing (Article 5(1)(a)). When businesses use personal data that are protected as a fundamental right, they are the ones who should ensure that the processing is legitimate. The protection of privacy requires that derogations and limitations must apply only in so far as is strictly necessary18 and exception must be narrowly construed.19

The businesses do not ‘own’ the personal data, nor are they otherwise entitled per se to process personal data.20 They are, however, allowed—with limitations and requirements laid out in the GDPR—to infringe on the citizen’s right to privacy.

In addition to serving a legitimate purpose, personal data must be processed fairly and be based on a ‘legitimate basis’, as dealt with immediately below under proportionality.

2.2.2. Proportionality

Due to the myriad guises that data processing may take, the principle of legitimacy is coupled with a proportionality principle that permeates the GDPR. The principle is visible in frequent references to what is ‘necessary’, ‘adequate’, ‘appropriate’, ‘compatible’, ‘reasonable’, etc.21

The legitimacy of processing depends on the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing as well as the risks of varying likelihood and severity for the rights and freedoms of natural persons. The rules aim to strike the appropriate balance between the protection of the data subject’s rights and the legitimate interests of data controllers and third parties and the interests of the public. For example, the same video surveillance may be lawful for security reasons, but unlawful for marketing purposes.

According to the general principles laid out in Article 5, personal data should be limited to what is necessary (‘data minimisation’) and not kept longer than necessary (‘storage limitation’). In this context, necessity is relative to ‘the purposes for which the personal data are processed’, as discussed above under legitimacy.

The principle of purpose limitation, introduced above, provides that personal data may not be further processed ‘in a manner that is incompatible with’ the purposes for which they are collected,22 which also reflects a proportionality test.

As mentioned, the processing of personal data must be based on the data subject’s consent or (notably!) some other legitimate basis laid down by law. There must be a legitimate basis (also ‘legal basis’; here, we use the Charter’s terminology) for each purpose for which personal data are processed.

GDPR Article 6(1) on ‘lawfulness of processing’ [emphasis added]:

1. Processing shall be lawful only if and to the extent that at least one of the following applies:

(a) the data subject has given consent to the processing of his or her personal data for one or more specific purposes;

(b) processing is necessary for the performance of a contract to which the data subject is party […];

(c) processing is necessary for compliance with a legal obligation to which the controller is subject; […]

(f) processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data […].

Consent requires a ‘freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject's wishes’ which ‘signifies agreement to the processing’.23 The request for consent must be ‘presented in a manner which is clearly distinguishable from […] other matters’, and consent may be withdrawn ‘at any time’ (Article 7).

Personal data can be processed (without consent) if this is necessary for, inter alia, the performance of a contract or compliance with a legal obligation. Together, these legitimate bases justify processing that is necessary for delivering products and complying with tax and accounting obligations.

Processing is also lawful (without consent), if it passes the balancing test, which—to some extent—can be used to justify processing for marketing purposes. The balancing test (Article 6(1)(f)) allows the data controller to process personal data when the processing is necessary for (legitimate) purposes, unless these interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject.

The term ‘necessity’ has it own independent meaning in EU law and must be interpreted in a manner that reflects the objectives of data protection law.24

As discussed below under ‘empowerment’, consent and the balancing test share the ‘disadvantage’ that the data subject may object to the processing, in the former case by means of withdrawing consent. The data subject cannot object if the processing is (genuinely) necessary for the performance of a contract. When processing sensitive personal data for marketing purposes,25 consent must always be obtained. This includes, e.g. big data analyses intended to extract ‘sensitive data’ from ‘normal data’.

Proportionality also plays a role in connection with the data controller’s general obligations (Chapter IV GDPR), which are dealt with below under ‘accountability’. When determining the responsibility of the data controller (Articles 24 and 25), account must be taken of ‘the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing as well as the risks of varying likelihood and severity for the rights and freedoms of natural persons’. For implementing certain measures, additional account must also be taken of ‘the state of the art’ and ‘the cost of implementation’ (Articles 25 and 32).

As dealt with below under ‘security’, technical and organisational measures must be ‘appropriate’ (Article 5(1)(f)), and in the context of rectification and erasure (Section 3, dealt with below under ‘empowerment’), account must be taken of ‘available technology and the cost of implementation’ as well as ‘disproportionate effort’.

As a general principle, it follows from Article 52(1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union that limitations to the freedoms set out in the Charter must—‘subject to the principle of proportionality’—be necessary and must genuinely meet (a) objectives of general interest recognised by the Union or (b) the need to protect the rights and freedoms of others.

Borrowing freely from Article 5(1) TEU, the proportionality principle would entail that the processing of personal data must not exceed what is necessary to achieve the (legitimate) objectives. In that vein, the availability of less intrusive means should also be considered.26 This is e.g. clear in the GDPR when it requires ‘appropriate safeguards’, which may include pseudonymisation.27

2.2.3. Empowerment

As discussed in Chapter 8 (manipulation), human agency and the right to self-determination are central concepts in legal theory as well as in consumer protection law, where the regulatory framework is aimed at empowering the consumer to act in accordance with his goals, values and preferences. Despite a principle of empowerment, the data subject does not have absolute control over what data are being processed about him and by whom. Here, we primarily focus on the data subject’s rights, which are closely coupled with ‘transparency’, dealt with below.

It is a popular mistake to assume that the data subject ‘owns’ his personal data and that the data amount to a currency, which can be used as payment. The Charter provides for ‘respect of privacy’ and ‘protection of personal data’, which does not amount to ownership (in a legal sense) where title can be transferred.28 Personal data as payment may, however, be a helpful metaphor in the context of weighing up of interest as discussed above under ‘proportionality’. Issues pertaining to owning and paying with personal data are discussed in Chapter 5 (marketing law) and Chapter 9 (transparency).

Consent is one of the clearest examples of ‘empowerment’.29 In addition to being specific and informed, consent must be freely given and constitute an ‘unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes’ that ‘signifies agreement to the processing of personal data’ (Article 4(1)(11)). Consent requires both transparency and a clear affirmative action which precludes ‘silence, pre-ticked boxes or inactivity’ from constituting consent.30

‘Freely given’ in the context of consent requires a genuinely free choice, which is not the case if the data subject is ‘unable to refuse or withdraw consent without detriment’ (recital 42). Similarly, it is provided in Article 7(4) that ‘utmost account’ must be taken of whether, inter alia, the performance of a contract is conditional on consent that goes beyond what is ‘necessary for the performance of that contract’.

In addition to situations where consent is required, the data subject is empowered through rights concerning access, rectification, erasure and objection. The first two rights are enshrined in Article 8(2) of the Charter. The data subject has the right to obtain confirmation as to whether or not personal data concerning him are being processed. If personal data about the data subject are being processed, the data subject has a right of access to the personal data as well as information about the purposes, categories, envisaged storage period and other information detailed in Article 15.

The right to obtain rectification of inaccurate personal data (without undue delay) is found in Article 16 and is well aligned with the accuracy principle, mentioned above under ‘legitimacy’. The so-called ‘right to be forgotten’ in Article 17 entails that the data subject can request the deletion of even accurate data (without undue delay). The right is, however, limited to certain grounds, including that the data are no longer necessary for the purpose or consent is withdrawn (and there is no other legal ground for the processing). The data controller may irreversibly anonymise the data to honour the request.

As mentioned above under ‘proportionality’, the data subject may withdraw his consent at any time (Article 7(3)). When the balancing test provides the legitimate basis for processing, the data subject has the right to object to the processing (Article 21(1)). The data controller must comply, unless he ‘demonstrates compelling legitimate grounds for the processing which override the interests, rights and freedoms of the data subject’. Where personal data are processed for direct marketing purposes, the data subject may object at any time to such marketing, which includes related profiling.

The use of cookies and e-mail for marketing purposes is regulated in the ePrivacy Directive31 (Articles 5 and 13, respectively) and consent is usually required, as discussed below under 3.3. Cookies may be stored and accessed without consent ‘where the technical storage or access is strictly necessary [to enable] the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user’.32

Other rights include a right to data portability (Article 20) and not being subject to automated individual decision-making, including profiling (Article 22), as discussed below under 4.

2.2.4. Transparency

Transparency is an important general feature of EU law, as discussed in Chapter 9 (transparency), and transparent processing of personal data is a prerequisite for ‘accountability’ towards authorities as well as ‘empowerment’ of the data subject.33 The principle is closely linked to both legitimacy and proportionality. Transparency is also an important part of consent that must be both specific and informed. In addition, the request for consent must be presented in a manner which is clearly distinguishable from other matters, such as contractual terms (Article 7(2)).

Articles 13 and 14 contain comprehensive information requirements to inform the data subject about the data controller’s identity and contact details, purposes for and categories of personal data processed, and the data subject’s rights, as well as other information ‘necessary to ensure fair and transparent processing in respect of the data subject’. When the data controller relies on the balancing test as legitimate basis, the data subject must be informed about the legitimate interests pursued.

In the context of ‘automated decision-making, including profiling’ (Article 22; discussed below under 4), transparency entails providing ‘meaningful information about the logic involved’, as well as ‘the significance and the envisaged consequences of such processing for the data subject’. This obligation could serve as inspiration for ensuring overall transparency in the context of data-driven business models, as discussed in Chapter 9 (transparency).

The data subject’s right to object to the processing of personal data for direct marketing purposes and/or based on the balancing test must explicitly be brought to attention at the time of the first communication with the data subject at the latest (Article 21(4)). Similarly, the data subject must—prior to giving consent—be informed about his right to withdraw consent (at any time)(Article 7(3)).

Information provided to the data subject must be in writing—or by other means, including electronically—and must be provided in a ‘concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language’ (Article 12(1)). The GDPR does not require the data controller to post a privacy policy on their website, but it is often an efficient way of informing the data subject—for instance, by means of a hyperlink—and also of organising the record of processing activities discussed immediately below under ‘accountability’.

2.2.5. Accountability

A significant part of the GDPR’s substantive rules stems from the 1995 data protection directive, now replaced by the GDPR. One significant change is made clear in Article 5(2), which provides that the data controller is not only responsible for compliance, but must also be able to demonstrate compliance. This principle is substantiated in Article 24, according to which, the data controller must implement ‘appropriate technical and organisational measures’ to (a) ensure and (b) be able to demonstrate that processing is performed in accordance with the GDPR.

These measures must be kept up to date and, as discussed above under ‘proportionality’, must take into account the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing. Risks of varying likelihood and severity to the rights and freedoms of natural persons must also be considered. The implementation of these measures must—‘when proportionate’—include ‘appropriate data protection policies’. In connection with consent, it is required that the data controller be ‘able to demonstrate’ that the data subject has consented to processing (Article 7(1)).

One of the most concrete measures of accountability is found in the requirement of maintaining a ‘record of processing activities’ (Article 30). The record must be in writing, including in electronic form, and must contain (a) the name and contact details of the data controller, (b) the purposes (note that this is in plural) of the processing, (c) a description of the categories of data subjects and of the categories of personal data, (d) categories of recipients to whom the personal data may be disclosed and (e) possible transfers of personal data to third countries (i.e. outside the European Union and the European Economic Area). ‘Where possible’, the record must also include (f) the envisaged time limits for erasure of the different categories of data and (g) a general description of the technical and organisational security measures.34 The record of processing activities must be available to the supervisory authority (on request), but there is no obligation to publish it, for instance in the guise of a privacy policy, as suggested above under ‘transparency’.

Prior to the processing of personal data that is ‘likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons’, the data processor must carry out a ‘Data Protection Impact Assessment’ (DPIA) of the envisaged processing (Article 35). This is, inter alia, required in the case of ‘a systematic and extensive evaluation of personal aspects relating to natural persons which is based on automated processing, including profiling, and on which decisions are based that produce legal effects’. If the assessment indicates that the processing would result in a high risk in the absence of measures taken by the data controller to mitigate the risk, the data controller must consult the supervisory authority prior to processing (Article 36).

In certain situations, the data controller is obliged to designate a ‘data protection officer’, including in cases where ‘the core activities […] consist of processing operations which, by virtue of their nature, their scope and/or their purposes, require regular and systematic monitoring of data subjects on a large scale’ (Article 37). These requirements can also be viewed as examples of proportionality as discussed above.

Compliance is further supported by the requirement of data protection by design and by default (Article 25).35 The data controller must implement ‘appropriate technical and organisational measures’ to (1) ensure compliance, (2) integrate necessary safeguards and (3) ensure that only necessary personal data are processed by default (settings). This provision is new to the GDPR and corroborates all six principles; just add ‘by design’ after each of the six principles.

2.2.6. Security

Securing personal data is of paramount importance in order to avoid the risk of e.g. accidental/unlawful destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorised disclosure of, or access to personal data transmitted, stored or otherwise processed. In this book we focus on traders that rely on data-driven business models to extract value from (personal) data. However, in many cases, the real threat in the context of personal data is not the data controller’s exploitation, but rather lack of security measures resulting in data breaches and subsequent exploitation by third parties, including employees and subcontractors. Thus, ‘data minimisation’ and ‘storage limitation’, discussed above under ‘proportionality’, as well as anonymisation and pseudonymisation, may be perceived as means to comply with the security principle.36

Edward Snowden’s surveillance revelations mentioned in Chapter 1 (why this book?) have shown that personal data collected by businesses may also be accessed by governments—with or without the cooperation of the business.

The data controller must implement ‘appropriate technical and organisational measures to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk’.37 Account must be taken of ‘the state of the art, the costs of implementation and the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing as well as the risk of varying likelihood and severity for the rights and freedoms of natural persons’, as discussed above under ‘proportionality’. Security measures may include (Article 32(1)):

the pseudonymisation and encryption of personal data;

the ability to ensure the ongoing confidentiality, integrity, availability and resilience of processing systems and services;

the ability to restore the availability and access to personal data in a timely manner in the event of a physical or technical incident;

a process for regularly testing, assessing and evaluating the effectiveness of technical and organisational measures for ensuring the security of the processing.

The data processor must take steps to ensure that any natural person acting under the authority of the data controller or the data processor, who has access to personal data, does not process them except on instructions from the data controller (Article 32(4)).

In case of a ‘personal data breach’, the data controller must (without undue delay) notify the supervisory authority (Article 33) and data subjects (Article 34) where there is a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons. In line with the proportionality principle, the latter must only be informed when the personal data breach is likely to result in ‘a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons’.38

3. Legitimate basis for data-driven marketing

In the context of data-driven business models, ‘consent’, ‘contractual necessity’ and ‘the balancing test’ are the most relevant legitimate bases. As mentioned above, the balancing test and consent share the disadvantage (from the trader’s perspective) that the user may object to the processing or withdraw consent, respectively.39 This is not possible for contractual necessity. From the data subject’s perspective, contractual necessity and the balancing test have the disadvantage that the data subject cannot take advantage of the provisions concerning data portability (Article 20 GDPR) that allow users to transfer personal data to another service provider.

As mentioned above, the term ‘necessary’ has its own independent meaning in EU law and must be interpreted in a manner that reflects the objectives of data protection law.40 It is ‘settled case-law’ that the protection of the fundamental right to privacy requires that derogations and limitations in relation to the protection of personal data must apply only in so far as is strictly necessary,41 and exceptions—such as the legitimate basis for infringing on privacy—must thus be narrowly construed.42

Sensitive personal data. Article 9(1) prohibits the processing of personal data revealing sensitive information (‘special categories of data’) that is exhaustively listed in the provision. This includes ethnic origin, political opinions, and religious and philosophical beliefs, as well as data concerning health and sexual orientation.

For the processing of sensitive personal data for marketing purposes, ‘explicit consent’ is necessary according to GDPR Article 9(2)(a). Thus, the trader cannot rely on contractual necessity or the balancing test. Because in many cases data—including e.g. a photo—may potentially reveal sensitive information,43 it is necessary to consider both the context and the intentions of the data controller to determine whether sensitive personal data are in fact processed.44 The following analyses focus on the processing of ‘normal’ personal data.

3.1. Contractual necessity

Article 6(1)(b) allows for processing of personal data (without consent) to the extent that the processing is ‘necessary for the performance of a contract’ with the data subject. Users cannot object if the processing is (genuinely) necessary for the performance of a contract but may decide to terminate the contract, which is not always a desirable option for them. This, in itself, calls for a strict interpretation.

The trader may rely on contractual necessity for delivering, for instance, a social media service, but the question is whether they can also rely on this legitimate basis to process data for personalised marketing with a view to funding the service. This is not settled in case law, but it seems peculiar when, for instance, Facebook insists that much of its extensive data processing for marketing purposes is ‘necessary’ for delivering its social media service.45

According to the EDPB, the interpretation of ‘necessary’ involves a ‘combined, fact-based assessment of the processing “for the objective pursued and of whether it is less intrusive compared to other options for achieving the same goal”’. Further, ‘if there are realistic, less intrusive alternatives, the processing is not “necessary”’.46 Thus, it is not sufficient that the processing be ‘useful’ or ‘necessary for the controller’s other business purposes’; it must be ‘objectively necessary for performing the contractual service’ in question.47 Merely mentioning data processing in a contract or otherwise artificially expanding the scope of processing in the contract does not constitute contractual necessity.48

Similarly, the EDPB finds—as a general rule—that processing of personal data for behavioural advertising is not necessary for the performance of a contract for online services,49 even when the advertising funds the service.50 A strict interpretation is also corroborated by the fact that the user’s right not to be subject to automated decisions, including profiling, does not apply in case of contractual necessity.51 The EDPB offers the following questions as guidance on whether contractual necessity can provide the proper legitimate basis:52

What is the nature of the service being provided to the data subject? What are its distinguishing characteristics?

What is the exact rationale of the contract (i.e. its substance and fundamental object)?

What are the essential elements of the contract?

What are the mutual perspectives and expectations of the parties to the contract? How is the service promoted or advertised to the data subject? Would an ordinary user of the service reasonably expect that, considering the nature of the service, the envisaged processing will take place in order to perform the contract to which they are a party?

The last item on the list seems to allow for the possibility that a mutual understanding—possibly created by means of marketing—may establish contractual necessity. However, this must be understood as relating to the possible scope of processing when no ‘realistic, less intrusive alternative’ exists. Thus, the processing in question must be an intrinsic element of the product as well as unavoidable and expected in order to rely on contractual necessity. The processing is not unavoidable if there are realistic, less intrusive alternatives.

As we discuss in Chapter 10 (human dignity and democracy), it should be possible to imagine realistic, less intrusive revenue models that rely on (a) subscription fees and/or (b) the reselling of attention without the processing of personal data and the surveillance of user behaviour. There may be better arguments for individualised marketing—including discounts—in a loyalty program, as this individualisation is likely to form an integral part of the product.

While we are waiting for the CJEU’s decision on this matter,53 it seems reasonable to assume that—at least for social media services and others who resell their users’ attention—contractual necessity is not the appropriate legal basis for (extensive) processing of personal data to personalise marketing, including by means of targeted advertising. Thus, the balancing test and consent should be considered, as they, ‘generally speaking’, are the two legitimate bases, ‘which could theoretically justify the processing that supports the targeting of social media users’.54

In a draft decision from 6 October 2021, the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC)55 found that ‘[…] Facebook is, in principle, entitled to rely on Article 6(1)(b) GDPR as a legal basis for the processing of a user’s data necessary for the provision of its service, including through the provision of behavioural advertising insofar as this forms a core part of that service offered to and accepted by the user under the contract between Facebook and its user.’56 A response from the EDPB, in the guise of a binding decision, is likely to be adopted in early 2022 (after the publication of this book),57 and it seems unlikely that the EDPB agrees with the DPC, as it would (a) be contrary to its own guidelines58 and (b) entail that the detailed requirement (safeguards) for consent can be circumvented by describing the envisaged processing in a contract.

3.1.1. Further processing

As a general principle, there must be a legitimate basis for each purpose for which personal data are processed. However, the purpose limitation principle in Article 5(1)(b) allows for ‘further processing’ as long as the processing is ‘not incompatible’ with the purposes for which the data are collected. ‘In such a case, no legal basis separate from that which allowed the collection of the personal data is required.’ (Recital 50).

For situations where the processing is not based on consent, Article 6(4) states that to ascertain whether processing for another purpose is compatible with the purpose for which the personal data were initially collected, the following must be taken into account:

any link between the purposes for which the personal data have been collected and the purposes of the intended further processing;

the context in which the personal data have been collected, in particular regarding the relationship between data subjects and the controller;

the nature of the personal data, in particular whether special categories of personal data are processed, pursuant to Article 9, or whether personal data related to criminal convictions and offences are processed, pursuant to Article 10;

the possible consequences of the intended further processing for data subjects;

the existence of appropriate safeguards, which may include encryption or pseudonymisation.

The new purpose may be compatible if it

‘correlates to the initial purpose in the sense that these purposes usually are pursued “together” in close vicinity in a timely as well as contextual sense, or that the further purpose is the logical consequence of the initial purpose’, i.e. depending ‘to a high degree on what is usual and what is to be expected’ and ‘further processing must not result in a substantively higher risk than the initial lawful processing’.59

There may be a natural link between the primary and ancillary products in data-driven business models, and the processing may very well be usual and expected by the data subject. On the other hand, as we discuss in Chapter 9 (transparency), the consequences of the processing relating to personalised marketing may not be as obvious as the consequences for the processing that is necessary for delivering the primary product. In addition, it could be argued that the trader should have foreseen the use of personal data for marketing purposes at the time of collection, and therefore should have established—in accordance with the principle of accountability—the proper legitimate basis before the processing took place.

When the requested service can be provided without the specific processing taking place for marketing purposes, the data controller must rely on either consent or the balancing test, which must be determined and conveyed to the data subject at the outset of the processing.60 This resonates with the argument that contractual necessity is not the proper legitimate basis for personalised marketing, when realistic and less intrusive alternatives exist.

It cannot be ruled out that some ‘further processing’ for marketing purposes may be ‘not incompatible’ with delivering the primary product. However, due to the need for a careful consideration of the privacy implications and a restrictive interpretation of this fundamental right, the processing must have an insignificant impact on privacy; possibly corresponding to what can be justified under the balancing test as well as under other applicable legislation such as the ePrivacy Directive concerning cookies and direct marketing, as discussed below.

3.2. The balancing test

The processing of personal data (without consent) is also lawful if it passes the balancing test,61 which—to some extent—can justify processing for marketing purposes. The balancing test allows the data controller to process personal data when the processing is necessary for (legitimate) purposes, unless these interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject. This test requires that the following cumulative conditions be met:

a legitimate interest must be pursued,

there must be a need to process the personal data for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued, and

the fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject do not take precedence.62

The balancing test may be perceived as a proportionality test where the processing of personal data is relative to the legitimate purpose pursued as well as to the impact on the data subject’s right to privacy—including the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing. The assessment under the balancing test resembles that of ‘further processing’, as GDPR recital 47 provides that the legitimate interests of the data controller could ‘in particular’ be overridden ‘where data subjects do not reasonably expect further processing’. The privacy impact must be limited and ‘the relationship with the controller’ must be considered together with the consequences and risks for the data subject. Including ‘reasonable expectation’ seems more appropriate for a proportionality test than for determining contractual necessity as discussed above.

It is expressly mentioned in recital 47 that ‘the processing of personal data for direct marketing purposes may be regarded as carried out for a legitimate interest’ (emphasis added). ‘The existence of a legitimate interest would need careful assessment including whether a data subject can reasonably expect at the time and in the context of the collection of the personal data that processing for that purpose may take place’ (emphasis added).

It is obvious that the processing has a more serious privacy impact when information relating to the data subject’s private life—as in most data-driven business models—is inferred from the data subject’s behaviour rather than obtained from public sources63 or directly from the data subject. In this vein, the principle of data minimisation may also weigh in favour of the data subject’s rights and interests.64 Finally, the availability of less intrusive means must also be considered.65

Thus, more intrusive and opaque processing of personal data, including surveillance, profiling and automated decisions, is likely to require consent unless the processing is genuinely necessary for the performance of a contract with the data subject or the impact on the data subject’s privacy is limited. When the processing is in fact necessary for the performance of a contract, however, consent is not the appropriate legitimate basis.66

3.3. Consent

Consent requires a ‘freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes’, which ‘signifies agreement to the processing’.67 The request for consent must be ‘presented in a manner which is clearly distinguishable from […] other matter’ (Article 7(2)), and consent may be withdrawn ‘at any time’ (Article 7(3)). When the processing has multiple purposes, consent should be given for each purpose (recital 32, the principle of ‘granularity’). The data controller must be able to demonstrate that the data subject has consented to processing of their personal data (Article 7(1)).

The use of cookies (storing and/or gaining access to information stored in the subscriber’s terminal equipment) and e-mail for direct marketing purposes is regulated in the ePrivacy Directive,68 and consent is usually required.69 Cookies can be stored/accessed without consent where it is ‘strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user’ (emphasis added).70

In contrast to the GDPR, the ePrivacy Directive is not limited to the processing of personal data but provides protection of privacy in a broader sense (interfering with the private sphere).71 The rules on cookies concern ‘any information’ stored on ‘terminal equipment’.

Consent under the ePrivacy Directive (cookies and direct marketing) should be understood in the same manner as under the GDPR. This was confirmed in Planet49,72 which is the leading case on consent in this context (its conclusions are incorporated below):

The Planet49 case concerned an online promotional lottery in which participation required that at least the first of two checkboxes was ticked. The checkboxes concerned (1) being contacted by sponsors and cooperation partners by email, post and/or telephone (not pre-ticked) and (2) the use of cookies to track behaviour across websites for marketing purposes (pre-ticked). By means of clicking a hyperlink associated with the first checkbox, the user could unsubscribe individually to each of 57 companies.

Consent has the advantage that it provides documentation as well as clarity concerning the legitimate basis, which must be determined before the collection of personal data. Generally speaking, consent must constitute a genuine and informed choice,73 as discussed below.

Despite consent, the processing of personal data is still restricted by the principles for lawful, fair and transparent processing (Article 5), including purpose limitation, data minimisation, accuracy and storage limitation, i.e. the processing must still be legitimate and proportionate. Surveillance of consumer behaviour and certain forms of personalised marketing may be unlawful—even when the user is willing to consent—especially when the activity affects human dignity and democracy, as discussed in Chapter 10 (human dignity and democracy). The general principles in Article 5 are important, as infringements hereof are in themselves subject to the highest fines provided for under the GDPR.74

3.3.1. Genuine choice

Consent requires a clear affirmative act, which may include ‘ticking a box’, but silence, pre-ticked boxes and inactivity cannot constitute consent (recital 32 GDPR). The arguments against pre-ticked boxes include that it would otherwise be ‘impossible in practice to ascertain objectively’ whether consent is given.75 It follows from recital 42 GDPR that consent is not freely given ‘if the data subject has no genuine or free choice or is unable to refuse or withdraw consent without detriment’ (emphasis added).76 The interpretation and assessment of ‘detriment’ is not easy, yet it is nevertheless important.

Data-driven business models are—at least to some extent—based on a mutual understanding of quid pro quo, as in ‘paying with personal data’, i.e. an acceptable trade-off. At the two extremes of how ‘detriment’ can be interpreted lie the possibilities that (a) the trader can ask for virtually anything (respecting the general principles in Article 5), as long as the data subject (genuinely) agrees to this and (b) even the slightest detriment is unlawful, including the offering of a paid-for version of the service where such payment would be a detriment. The truth is likely to be somewhere in between.

When assessing whether consent is freely given, Article 7(4) provides that ‘utmost account shall be taken of whether, inter alia [i.e. other criteria may be relevant], the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is conditional on consent to the processing of personal data that is not necessary for the performance of that contract’ (emphasis and comment added). It has been suggested that Article 7(4) codifies a ‘prohibition on bundling’, which—due to the term ‘utmost account’—is not ‘absolute in nature’.77 Consent is ‘presumed not to be freely given if it does not allow separate consent to be given to different personal data processing operations despite it being appropriate in the individual case, or if the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is dependent on the consent despite such consent not being necessary for such performance.’78

The provision seems to justify the notion that consent to the processing of (unnecessary) personal data can be made conditional for the performance of the contract in some instances. However, when consent is conditional on the performance of a contract, the consent cannot be withdrawn ‘without detriment’, and thus Article 7(4) seems to widen the scope of contractual necessity beyond what is strictly necessary for the contractual performance. The CJEU seems to regret that this question was not asked in the Planet49 case.79

Given the aims of data protection law, there must be a ‘strong presumption’ against the processing of personal data being a ‘mandatory consideration in exchange for the performance of a contract’.80 The EDPB rules out that consent can be freely given when cookie walls are in place, i.e. when access to services and functionalities is made conditional on consent.81 According to the Board, this is not affected by other market actors offering alternatives where ‘consent’ is not required.82

The term ‘presumed’ indicates that such cases are ‘highly exceptional’—but ‘does not preclude all incentives’83—and that ‘in any event, the burden of proof in Article 7(4) is on the controller’.84 Similarly, recital 25 of the ePrivacy Directive provides that ‘access to specific website content may still be made conditional on the well-informed acceptance of a cookie or similar device, if it is used for a legitimate purpose.’

In the proposal for an ePrivacy Regulation, it is suggested that ‘where access is provided without direct monetary payment and is made dependent on [the usage of cookies] for additional purposes, requiring such consent would normally not be considered as depriving the end-user of a genuine choice if the end-user is able to choose between services, on the basis of clear, precise and user-friendly information about the purposes of cookies and similar techniques, between [(a)] an offer that includes consenting to the use of cookies for additional purposes on the one hand, and [(b)] an equivalent offer by the same provider that does not involve consenting to data use for additional purposes, on the other hand.’

It is, however, noted that ‘in some cases, making access to website content dependent on consent to the use of such cookies may be considered, in the presence of a clear imbalance between the end-user and the service provider as depriving the end-user of a genuine choice. […] such imbalance could exist where the end-user has only few or no alternatives to the service, and thus has no real choice as to the usage of cookies for instance in case of service providers in a dominant position.’85

To support the case against ‘mandatory consent’ (recognising the contradiction in terms) recital 43 GDPR provides that

‘consent is presumed not to be freely given if it does not allow separate consent to be given to different personal data processing operations despite it being appropriate in the individual case, or if the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is dependent on the consent despite such consent not being necessary for such performance.’

A genuine choice may also be questioned in situations where there is a ‘clear imbalance’ in power between the data controller and the data subject. In order to ensure that consent is freely given, GDPR recital 43 provides that in such situations ‘consent should not provide a valid legal ground […]’. In particular, the provision is relevant where the controller is a public authority or an employer.

A clear imbalance in power is also likely to occur in business-to-consumer relationships, which is the rationale behind much consumer protection law as described in Chapter 3 (regulating markets). Even though there is a notorious imbalance between trader and consumer, the consumer may, however, feel less compelled to accept any request for consent compared with an employee.

The use of social media services may be important not only for social and personal purposes (‘psychological needs’, including social belonging and ‘self-fulfilment needs’86), but also for carrying out civic duties in a democracy, especially when these media platforms are used for dissemination and engagement by governments, authorities, politicians, media organisations, universities, schools, etc.

In offline loyalty schemes, a clear imbalance in power may be less obvious because there are usually meaningful/believable alternatives to, e.g. a grocery store, even when that particular store is more convenient in terms of, e.g. proximity, price, quality, service and variety. In some situations, consumers may ‘decide’ to ‘trade privacy for convenience or discounts’, and the genuineness of the choice may be debatable. This is particularly true when the store explicitly displays discounts to members of their loyalty program (‘Price €12, members pay only €8’) and/or when all meaningful alternatives have similar, semi-mandatory loyalty schemes.

This discussion is similarly relevant in the context of whether there is a ‘detriment’ to not consenting. Enjoying less selection, having to pay more and travelling further would be detriments to most of us, especially when purchasing such daily necessities as food and medicine, etc. In particular in ongoing B2C relationships, including subscription services, dependency may increase as a function of time. This is both because the status quo is convenient (frictionless) and also due to accrued credits/credentials, dependency on certain facilities, and sunk costs related to networks and history, including uploaded material.

Consent—for legitimate and proportionate processing—is not problematic when (a) the consent is properly informed, (b) the user can withdraw consent to the processing of personal data for marketing purposes without detriment and (c) the user is properly informed about the right to withdraw consent. These discussions are further pursued in Chapter 8 (manipulation).

3.3.2. Informed choice

Pursuant to the definition, consent must be a ‘specific’ and ‘informed’ indication of the data subject’s wishes. Recital 42 provides that ‘for consent to be informed, the data subject should be aware at least of the identity of the controller and the purposes of the processing for which the personal data are intended.’

That consent must be an informed choice is closely related to and a prerequisite for a genuine choice to be made. In this vein, the information requirements must be proportionate to, inter alia, the average data subject’s reasonable expectations and the impact on their right to privacy. These discussions are further pursued in Chapter 9 (transparency).

4. Automated individual decision-making, including profiling

GDPR Article 22 provides that the data subject has the right ‘not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects him or her’ (emphasis added). The provision is assumed to imply an ‘in-principle prohibition of such decisions’.87 In recital 71, ‘automatic refusal of an online credit application’ and ‘e-recruiting practices’ are mentioned as well as

‘“profiling” that consists of any form of automated processing of personal data evaluating the personal aspects relating to a natural person, in particular to analyse or predict aspects concerning the data subject’s performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences or interests, reliability or behaviour, location or movements’ (emphasis added).

This provision does not apply if the decision is based on contractual necessity or ‘explicit consent’, but suitable safeguards must be in place, including ‘at least the right to obtain human intervention’.

The extent to which personalised marketing may have legal or ‘similar effect’ is not settled case law. However, being exposed or not exposed to particular offers may have real economic effects. The decision must have ‘the potential to significantly influence the circumstances, behaviour or choices of the individuals concerned’ and may, ‘at its most extreme’, lead to the ‘exclusion or discrimination of individuals’. Examples may include automated decision-making that results in ‘differential pricing based on personal data or personal characteristics’ if, for example, ‘prohibitively high prices effectively bar someone from certain goods or services’.88

There are no obvious reasons why this should not apply to personalised marketing, including at least some forms of targeted advertising. According to the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, the decision to present targeted advertising based on profiling may have a ‘similarly significant effect’ on individuals, depending upon the particular characteristics of the case, including:89

the intrusiveness of the profiling process, including the tracking of individuals across different websites, devices and services;

the expectations and wishes of the individuals concerned;

the way the advertisement is delivered; or

using knowledge of the vulnerabilities of the data subjects targeted.

In the same vein, it is emphasised that processing, which might have little impact on individuals generally, may in fact have a significant effect on certain groups of society, such as minority groups or vulnerable adults.90

It seems reasonable to conclude that personalised marketing—at least to some extent—amounts to automated individual decision-making, including profiling that has legal or similar effects.91 It is also clear from this provision that such decisions have a (potentially) high impact on the data subject’s privacy and circumstances, including ‘personal welfare’.92 Contractual necessity and explicit consent must be interpreted as equally restrictive.93

1. See, e.g., Alan F. Westin, Privacy and Freedom (Atheneum 1967). See also Sarah I. Igo, The Known Citizen (Harvard University Press 2018) and Vance Packard, The Naked Society (Ig Publishing 2014, first published 1964).

2. Alan F. Westin, Privacy and Freedom (Atheneum 1967), p. 39; and Sarah E. Igo, The Known Citizen (Harvard 2018), p. 15.

3. Samuel D. Warren & Louis D. Brandeis, ‘The Right to Privacy’, Harvard Law Review, 1890, Vol. IV, pp 193–220.

4. Ibid.

5. Alan F. Westin, Privacy and Freedom (Atheneum 1967), p. 7.

6. Ibid., pp. 35, 57 and 161, respectively.

7. Signed

28 January 1981 in Strasbourg,

<https://www.coe.int/en/web/data-

protection/convention108-and-protocol>.

8. Article 6 TEU as amended by the Treaty of Lisbon signed 13 December 2007.

9. Directive 95/46/EC on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. Case law concerning this Directive remains relevant, as many of its principles are upheld in the GDPR.

10. See also recitals 40–41 GDPR.

11. This is not meant as personal data flowing unrestricted, but is a reference to the European single market, where data protection law should not hinder cross-border trade.

12. Article 288 TFEU provides that a regulation has ‘general application’ and is ‘binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States’. With regard to the territorial scope, see Article 3 GDPR.

13. Case C‑434/16, Nowak, ECLI:EU:C:2017:994, paragraph 35 (emphasis added).

14. See, e.g. Cases C‑131/12, Google Spain and Google, ECLI:EU:C:2014:317; C‑210/16, Wirtschaftsakademie Schleswig-Holstein, ECLI:EU:C:2018:388 (fan page operator on Facebook); and C‑40/17, Fashion ID, ECLI:EU:C:2019:629 (Facebook Social Plugins).

15. See e.g. opinion of Advocate General Szpunar in Case C‑673/17, Planet49, ECLI:EU:C:2019:246, paragraph 81, referring to ‘the non-binding but nevertheless enlightening work’ of the Article 29 Working Party (now replaced by the EDPB).

16. Article 5 GDPR prescribes seven general principles that are incorporated into the text. These principles do not summarise the GDPR or carry equal weight. See also the eight principles of the 1980 OECD Privacy Guidelines (updated in 2013) may. For more traditional introductions to the GDPR, see e.g. Jan Trzaskowski & Max Gersvang Sørensen, GDPR Compliance (Ex Tuto 2019) and Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave & Christopher Docksey (eds), The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Oxford University Press 2020).

17. Jan Trzaskowski, ‘GDPR Compliant Processing of Big Data in Small Business’, in Carsten Lund Pedersen, Adam Lindgreen, Thomas Ritter & Torsten Ringberg (eds), Big Data in Small Business—Data-Driven Growth in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (Edward Elgar 2021).

18. Case C‑473/12, IPI, ECLI:EU:C:2013:715, paragraph 39 with references.

19. Case C‑212/13, Ryneš, ECLI:EU:C:2014:2428, paragraph 29 with references.

20. See also Directive (EU) 2019/770 of 20 May 2019 on certain aspects concerning contracts for the supply of digital content and digital services, recital 24: ‘personal data cannot be considered as a commodity’.

21. See also EDPS, ‘Guidelines on assessing the proportionality of measures that limit the fundamental rights to privacy and to the protection of personal data’, 19 December 2019.

22. Article 5(1)(b). See also Article 6(4).

23. According to the definition in Article 4(1)(11). See also EDPB, ‘Guidelines 05/2020 on consent under Regulation 2016/679 (version 1.1)’.

24. Case C‑524/06, Huber, ECLI:EU:C:2008:724, paragraph 52.

25. Article 9. These ‘special categories of personal data’ comprise (exhaustively) personal data revealing ‘racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, or trade union membership, and the processing of genetic data, biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person, data concerning health or data concerning a natural person’s sex life or sexual orientation’.

26. See also Joined Cases C‑92/09 and C‑93/09, Volker und Markus Schecke and Eifert, ECLI:EU:C:2010:662.

27. Separation between identity and the data being processed, which is not the same as anonymisation. See also Article 29 Working Party’s Opinion 05/2014 on Anonymisation Techniques.

28. Cf. Article 17(1) of the Charter (the right to property) stating that ‘everyone has the right to own, use, dispose of and bequeath his or her lawfully acquired possessions’.

29. See also EDPB, ‘Guidelines 05/2020 on consent under Regulation 2016/679 (version 1.1)’.

30. Recital 32. See also Case C‑673/17, Planet49, ECLI:EU:C:2019:801.

31. See also proposal for an ePrivacy Regulation, 10 January 2017, COM/2017/010 final, 2017/03 (COD).

32. Recital 66 of Directive 2009/136/EC amending the ePrivacy Directive.

33. See also Article 29 Working Party ‘Guidelines on transparency under Regulation 2016/679’, WP260 rev.01, 11 April 2018.

34. Organisations with fewer than 250 employees need only maintain records of processing activities for the types of processing mentioned in items (a)–(c). See e.g. Article 29 Working Party, ‘Position paper on the derogations from the obligation to maintain records of processing activities pursuant to Article 30(5) GDPR’ (19 April 2018).

35. See also EDPB, ‘Guidelines 4/2019 on Article 25 Data Protection by Design and by Default (version 2.0)’.

36. See also Case C‑623/17, Privacy International, ECLI:EU:C:2020:790, paragraphs 68 and 73 with references.

37. Article 32, emphasis added. See similarly Article 5(1)(f).

38. See also Article 29 Working Party, ‘Guidelines on Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) and determining whether processing is “likely to result in a high risk” for the purposes of Regulation 2016/679’, WP 248 rev.01, 4 October 2017.

39. Consent can, according to Article 7(3), be withdrawn ‘at any time’, whereas objection to processing is regulated in Article 21.

40. Case C‑524/06, Huber, ECLI:EU:C:2008:724, paragraph 52.

41. Case C‑473/12, IPI, ECLI:EU:C:2013:715, paragraph 39 with references. Similarly Case C‑13/16, Rīgas satiksme, ECLI:EU:C:2017:336, paragraph 30; and Case C‑708/18, Asociaţia de Proprietari bloc M5A-ScaraA, ECLI:EU:C:2019:1064, paragraph 46.

42. Case C‑212/13, Ryneš, ECLI:EU:C:2014:2428, paragraph 29 with references.

43. See, e.g., Federal Trade Commission, ‘California Company Settles FTC Allegations It Deceived Consumers about use of Facial Recognition in Photo Storage App’, press release, 11 January 2021.

44. Similarly, Ludmila Georgieva & Kristopher Kuner, ‘Article 9. Processing of special categories of personal data’, in Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave & Christopher Docksey (eds), The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Oxford University Press 2020), p. 374 with references. See also Case C‑708/18, Asociaţia de Proprietari bloc M5A-ScaraA, ECLI:EU:C:2019:1064, paragraph 57.

45. ‘Terms of Service’ with reference to ‘Data Policy’ that directs users to ‘Learn more about these legal bases […]’, <https://www.facebook.com/legal/terms/>, <https://www.facebook.com/about/privacy> and <https://www.facebook.com/about/privacy/legal_bases> (visited [from Europe] October 2021).

46. With reference to Joined Cases C‑92/09 and C‑93/09, Volker und Markus Schecke and Eifert, ECLI:EU:C:2010:662.

47. EDPB,

‘Guidelines

2/2019 on the processing of personal data under Article

6(1)(b)

GDPR in the context of the provision of online services to data

subjects’, paragraphs 25 and 30. See

also Waltraut Kotschy, ‘Article 6. Lawfulness of processing’, in

Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave & Christopher Docksey (eds),

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Oxford

University Press 2020), p. 331.

48. EDPB,

‘Guidelines 2/2019 on the processing of personal data under

Article

6(1)(b) GDPR in the context of the provision of online

services to data subjects’, paragraphs 27 and 31.

49. Ibid., paragraph 52, adding: ‘Normally, it would be hard to argue that the contract had not been performed because there were no behavioural ads.’

50. Ibid., paragraph 53.

51. See below under 4.

52. EDPB,

‘Guidelines 2/2019 on the processing of personal data under

Article

6(1)(b) GDPR in the context of the provision of online

services to data subjects’, paragraph 33.

53. See, e.g., <https://noyb.eu/en/vienna-superior-court-facebook-must-give-access-data>.

54. Similarly EDPB, ‘Guidelines 08/2020 on the targeting of social media users (version 2.0)’, paragraph 49.

55. <https://www.dataprotection.ie/>.

56. Irish Data Protection Commission draft decision of 6 October 2021, paragraph 4.55.

57. The decision will be published on the EDBP’s website (<https://edpb.europa.eu/>), and is likely to be commented by NOYB—European Center for Digital Rights (<https://noyb.eu/en>).

58. EDPB,

‘Guidelines 2/2019 on the processing of personal data under

Article

6(1)(b) GDPR in the context of the provision of online

services to data subjects’, section 3.3.

59. Waltraut Kotschy, ‘Article 6. Lawfulness of processing’, in Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave & Christopher Docksey (eds), The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Oxford University Press 2020), pp. 341–342.

60. EDPB,

‘Guidelines 2/2019 on the processing of personal data under

Article

6(1)(b) GDPR in the context of the provision of online

services to data subjects’, paragraph 17.

61. Often, this legitimate basis is referred to as ‘legitimate interests’. This term is not used here as it (1) entails possible and unfortunate confusion with the general requirement of purpose limitation in Article 5(1)(b) and (2) obscures the fact that the data controller’s ‘legitimate interests’ must be balanced against the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject, as mentioned above.

62. Cases C‑13/16, Rīgas satiksme, ECLI:EU:C:2017:336, paragraph 28; and C‑708/18, Asociaţia de Proprietari bloc M5A-ScaraA, ECLI:EU:C:2019:1064, paragraph 40.

63. Similarly Case C‑708/18, Asociaţia de Proprietari bloc M5A-ScaraA, ECLI:EU:C:2019:1064, paragraph 55.

64. Case C‑708/18, Asociaţia de Proprietari bloc M5A-ScaraA, ECLI:EU:C:2019:1064, paragraph 48.

65. Case C‑708/18, Asociaţia de Proprietari bloc M5A-ScaraA, ECLI:EU:C:2019:1064, paragraph 47. See also Joined Cases C‑92/09 and C‑93/09, Volker und Markus Schecke and Eifert, ECLI:EU:C:2010:662.

66. EDPB,

‘Guidelines 2/2019 on the processing

of personal data under Article

6(1)(b) GDPR in the context of

the provision of online services to data subjects’, p. 7.

67. According to the definition in Article 4(1)(11).

68. Articles 5 and 13, respectively. See also proposal of 10 February 2021 for an ePrivacy Regulation, 6087/21, 2017/0003 (COD).

69. EDPB, ‘Guidelines 05/2020 on consent under Regulation 2016/679 (version 1.1)’, paragraph 6 with references. It is mentioned that consent is also likely to be needed for ‘most online marketing messages’.

70. Recital 66 of Directive 2009/136/EC amending the ePrivacy Directive.

71. Directive 2002/58, recital 24. See also Case C‑673/17, Planet49, ECLI:EU:C:2019:801, paragraphs 69 with reference to point 107 of Advocate General Szpunar’s opinion.

72. Case C‑673/17, Planet49, ECLI:EU:C:2019:801, paragraphs 38–43.

73. ‘Genuine choice’ can be said to comprise the requirements of ‘freely given’, ‘unambiguous indication’ and ‘signifying agreement’. Similarly, ‘informed choice’ comprises ‘specific’ and ‘informed’ indication.

74. See Article 85(5)(a) GDPR.

75. Case C‑673/17, Planet49, ECLI:EU:C:2019:801, paragraphs 49, 52 and 55.

76. See also Case C‑291/12, Schwarz, ECLI:EU:C:2013:670, paragraph 32.

77. Advocate General Szpunar’s opinion in Case C‑673/17, Planet49, ECLI:EU:C:2019:246, paragraphs 97–98.

78. Advocate General Szpunar’s opinion in Case C‑673/17, Planet49, ECLI:EU:C:2019:246, paragraphs 66 and 74–75.

79. Case C‑673/17, Planet49, ECLI:EU:C:2019:801, paragraph 64.

80. EDPB, ‘Guidelines 05/2020 on consent under Regulation 2016/679 (version 1.1)’, paragraphs 13 and 26–27. See also Frederik J. Zuiderveen Borgesius, Sanne Kruikemeier, Sophie C. Boerman & Natali Helberger, ‘Tracking Walls, Take-It-Or-Leave-It Choices, the GDPR, and the ePrivacy Regulation’, EDPL, 2017.

81. EDPB, ‘Guidelines 05/2020 on consent under Regulation 2016/679 (version 1.1)’, paragraph 39. Footnote omitted.

82. Ibid., paragraph 38.

83. Ibid., paragraph 48.

84. Ibid., paragraphs 35–36.

85. Proposal for an ePrivacy Regulation, 10 February 2021, 6087/21, 2017/0003 (COD), recital 20aaaa (emphasis added).

86. Cf. Abraham H. Maslow, ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’, Psychological Review, 50(4), 1943, pp. 370–96.

87. See Frederik Zuiderveen Borgesius, Discrimination, artificial intelligence, and algorithmic decision-making (Council of Europe 2018), p. 23 with references. This is, however, not settled case law. See also Isak Mendoza & Lee A. Bygrave, ‘The Right Not to be Subject to Automated Decisions Based on Profiling’, in Tatiana-Eleni Synodinou, Philippe Jougleux, Christiana Markou & Thalia Prastitou, EU Internet Law (Springer 2017).

88. Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, ‘Guidelines on Automated individual decision-making and Profiling for the purposes of Regulation 2016/679’, WP251rev.01, p. 11.

89. Ibid.

90. Ibid., p. 11.

91. See also ibid., pp. 21–22.

92. Lee A. Bygrave, ‘Article 22. Automated individual decision-making, including profiling’, in Christopher Kuner, Lee A. Bygrave & Christopher Docksey (eds), The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Oxford University Press 2020), p. 534.

93. Ibid.